Big cats like lions, jaguars, cheetahs, leopards and cougars hide their pain so they are less likely to be attacked when they are weak and eaten by other animals. Pet cats, which bear the same genes, act in the same way – making it difficult even for veterinarians to determine whether these domestic animals are suffering. House cats often suffer from chronic pain, but their owners find it hard to know and then don’t take them for medical treatment.

Now, researchers from the Tech4Animals lab at the University of Haifa, São Paulo University in Brazil and Lincoln University and Nottingham University in the UK have developed groundbreaking artificial intelligence able of identify pain in cats.

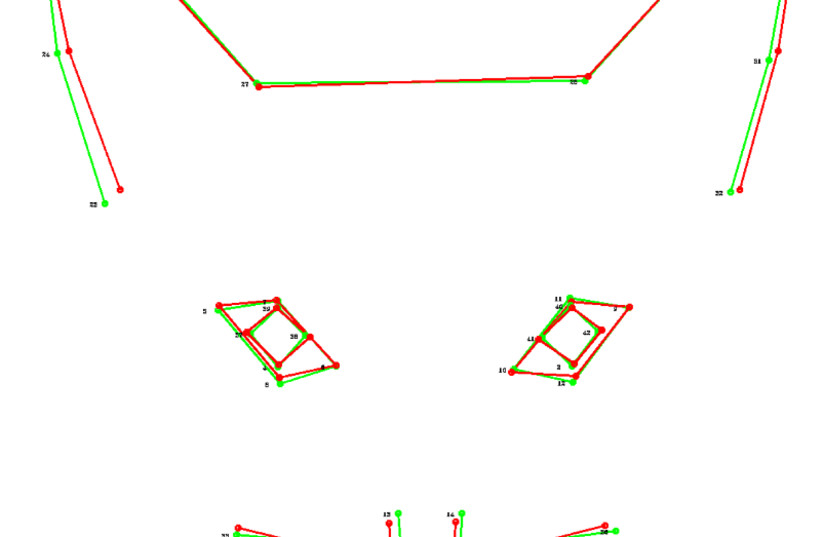

With the use of deep-learning models and facial recognition analysis, the researchers have achieved an impressive success rate of over 70% in identifying which cats are in pain. The methods were tested on 29 short-hair British cats, and the areas around the mouth and eyes were found to be most significant in identifying pain.

The international study involving researchers from the University of Haifa that was published in the prestigious journal Scientific Reports from the Nature group under the title “Automated recognition of pain in cats.” It was led by doctoral student Marcelo Feighelstein with his advisors Prof. Anna Zamansky and Prof. Ilan Shimshoni from the information systems department at the University of Haifa.

Developing the AI

The team photographed the female cats’ faces before and after sterilization, while they are still under the influence of painkillers, and after the painkillers have worn off. Models detected the subtle changes in facial expressions such as the tips of the ears, eyes, whisker and mustache that indicate pain.

“Facial expressions are identified as one of the most common and specific indicators of pain in human and non-human animals,” they wrote. Since Dale Langford and colleagues at McGill University in Montreal first reported on facial expressions associated with pain in mice there has been growing interest in tools for the assessment of facial expressions linked to pain in a range of non-human animal species. Such tools have been created and validated for various species, including rats, rabbits, horses, pigs, sheep and ferrets,” they wrote iin the paper.

This incredible breakthrough involving cats, the authors continued, has the potential to revolutionize the way we care for our feline friends, making it easier for anyone who has a cat to photograph them, without the need for physical contact, and to check reliably whether the cat is in pain.

There are some important challenges in using automated pain recognition in animals, which can also be generalized to emotion recognition in general, they wrote. “First of all, much less data is available, compared to the vast amounts of data in the human domain. Furthermore, particularly in the case of domesticated species selected for their aesthetic features, there may be comparatively much greater variation in their facial morphology, making population-level assessments problematic, due to the potential for pain-like facial features to be more present/absent in certain breeds at baseline. Finally – and perhaps most crucially – there is no verbal basis for establishing ground truth, whereas in humans, self-reporting is commonly used.”

The Tech4Animals Lab is working on a digital “Dr. Dolittl-E” app to detect animal feelings is showing how AI technology is advancing and transforming the world of veterinary care, and how it could help us better understand our animal companions.