Asteroid 3200 Phaethon is known to space researchers as resembling a comet, brightening and forming a tail when approaching the sun. It is also the source of the Geminid meteor shower that occurs annually - even though comets are usually the cause of meteor showers. Now, scientists have identified that this asteroid's abnormal habits are not as connected to the sun as previously thought.

According to a study published in the Planetary Science Journal, the tail of the Phaethon asteroid is not dust from being scorched by the sun, but rather sodium gas. This gives scientists a reason to believe that the gas is the reason for the asteroid's differential behavior.

“Our analysis shows that Phaethon’s comet-like activity cannot be explained by any kind of dust,” said study leader and California Institute of Technology PhD student Qicheng Zhang.

Asteroids are made up mostly of rocks, therefore keeping them from typically forming a tail when approaching the sun. Comets are different - they are comprised of both ice and rock and form tails near the sun as they are vaporized and blasting off any materials on their surface and producing a trail of anything in excess. They leave trails of this material in passing.

When Earth passes a debris trail, that's what creates what we see as a meteor shower - a swarm of shooting stars!

Phaethon was first discovered by astronomers in 1983 and quickly led them to recognize the orbit as matching the patterns similar to comets, though it was identified as an asteroid instead of a comet.

Back in in 2009, NASA’s Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO) spotted a short tail extending from Phaethon as the asteroid reached its closest point to the Sun (or “perihelion”) along its 524-day orbit. According to NASA, regular telescopes hadn’t spotted the tail before because it only forms when the asteroid is too close to the Sun to observe, and is only available to see in solar observatories.

STEREO noticed Phaethon’s tail develop on solar approaches that came in 2012 and 2016. The way the tail looked supported the theory that dust was escaping the asteroid’s surface when heated by the Sun.

Just a couple of years later, though, a 2018 solar mission captured images of the debris trail revealing something unexpected. NASA's Parker Solar Probe revealed that the trail had more material than Phaethon could realistically shed during approaches to the sun.

According to the research team responsible for the study, this was what sparked their interest in learning more about just what could cause this comet-like behavior.

“Comets often glow brilliantly by sodium emission when very near the Sun, so we suspected sodium could likewise serve a key role in Phaethon’s brightening,” Zhang said.

Thanks to previous research, models and lab tests suggested that the Sun's intense heat during Phaethon's close solar approaches would be able to vaporize sodium that existed within the asteroid, leading it to mimic comet activity.

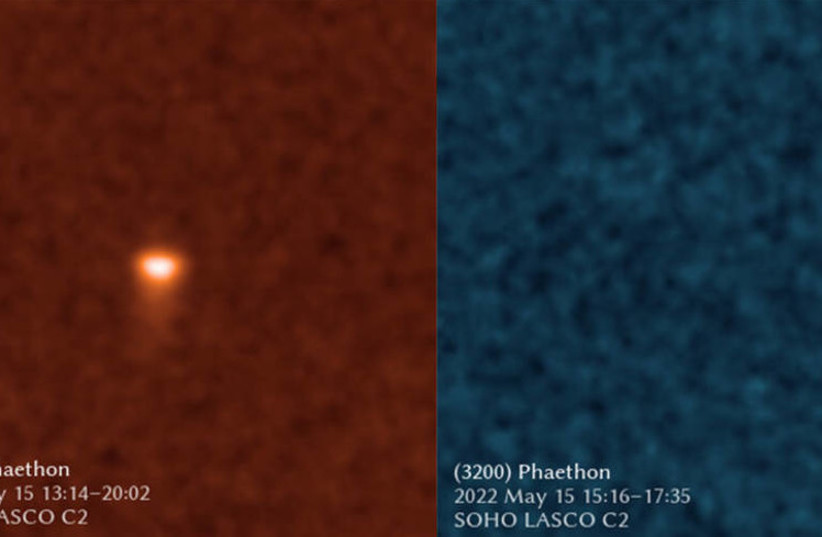

Years later in 2022, Zhang's team looked for this same pattern during Phaethon's latest solar approach. He used the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) spacecraft — a joint mission between NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) – complete with color filters able to detect both sodium and dust. Zhang's team tapped into archival images from STEREO and SOHO to identify the tail on the asteroid's 18 close solar approaches between 1997 and 2022.

Spacecraft observations reveal unique asteroid behaviors

SOHO's observations noticed that the asteroid's tail was much brighter in the sodium-detecting filter, though not in the dust-detecting filter. This, combined with the shape of the tail and the way the stream brightened when passing the sun provided evidence that the Phaethon's tail is made of sodium instead of dust.

“Not only do we have a really cool result that kind of upends 14 years of thinking about a well-scrutinized object,” said team member Karl Battams of the Naval Research Laboratory, “but we also did this using data from two heliophysics spacecraft – SOHO and STEREO – that were not at all intended to study phenomena like this.”

This has made Zhang and his team reconsider the identification of many "comets" identified by SOHO, wondering how many of them actually have earned that identification.

“A lot of those other sunskirting ‘comets’ may also not be ‘comets’ in the usual, icy body sense, but may instead be rocky asteroids like Phaethon heated up by the Sun,” Zhang explained.

However, there's still an important question: If Phaethon doesn't shed as much dust as previously though, how can it create the meteor shower effect seen every December?

Zhang's team believes the answer dates back to something disruptive from thousands of years ago. It is possible that part of the asteroid had broken apart under the asteroid's rotation, leading Phaethon to eject more than a billion tons of the material associated with the Geminid debris stream. Still, that initial event remains a mystery to scientists.

This study awaits follow-up research from an upcoming Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) mission called DESTINY+ (short for Demonstration and Experiment of Space Technology for Interplanetary voyage Phaethon fLyby and dUst Science). In the coming years, the DESTINY+ spacecraft is expected to fly past Phaethon, capturing images of its rocky surface and studying any dust that could be revealed around this puzzling asteroid.