No one – especially children – who read about the genius American inventor, writer, scientist, statesman, founding father, diplomat, printer, publisher and political philosopher Benjamin Franklin could fail to be in awe of him.

Yet, when looking at paintings that illustrated his scientific experiments, which play a fundamental role in both science education and the dissemination of scientific knowledge to the general public, one can be misled.

Confirming the adage that “a picture is worth a thousand words,” these depictions of famous experiments remain in the minds of those who study them and become definitive versions of the scientific process. Among these unforgettable images are Archimedes in the bath discovering the law of buoyancy; Isaac Newton refracting sunlight with a prism and defining the principles of modern optics; and Gregor Mendel cultivating peas and laying the foundations of genetics.

Many of these depictions convey false information, either because the experiments never actually happened or because they were performed quite differently. People who try to reproduce them on the basis of what the illustrations depict might not get any results at all or could even face dangerous consequences.

A study conducted by Breno Arsioli Moura, a researcher at the Federal University of the ABC in São Paulo, Brazil, investigated depictions of one of these famous experiments in which Franklin supposedly flew a kite in 1752 to draw electricity from a thundercloud.

An article on the study has just been published in the journal Science & Education under the title “Picturing Benjamin Franklin’s Kite Experiment in the Nineteenth Century.”

What do illustrations get wrong about Benjamin Franklin's kite experiment?

“The kite experiment is Franklin’s most famous scientific achievement,” said Moura. In fact, he added, the kite experiment was designed to be a simpler version of another experiment Franklin thought up in 1750 and that is now known as the “sentry box” experiment.”

“A kind of sentry box was to be set up on top of a tower, steeple or hill, and a man would stand inside it on an insulating dais made of wax, with a long, sharply pointed iron rod measuring some 10 meters inserted into it. Franklin expected the tip of the rod to ‘draw fire’ from the clouds. If the experimenter brought his knuckles close to the bottom of the rod, he would produce sparks,” Moura said. “It’s important to note two things. The experiment wasn’t to be performed during a storm to take advantage of lightning strikes, and the rod wasn’t to be earthed but anchored by the insulating stand so that all the electricity extracted would be stored in it.”

Franklin’s proposal stayed on paper until a highly similar experiment was performed by French researchers in 1752. Its success drew even more international attention to his work on electricity. “When he heard about the French experiment, Franklin wrote to a correspondent in England that a simpler version of the experiment – with the kite –had been performed in Philadelphia where he lived,” Moura continued.

The kite consisted of a “small cross made of two light strips of cedar, the arms so long as to reach to the four corners of a large thin silk handkerchief when extended”, Franklin wrote. A “very sharp-pointed wire” was tied to the “top of the upper stick of the cross, rising a foot or more above the wood”. The principle was the same as in the sentry box proposal. A key was fastened to the end of a silk ribbon, which in turn was tied to the end of the string (silk is an insulator).

“The experimenter held the apparatus by the silk ribbon so that electricity drawn down ‘silently’ from the clouds by the kite and conveyed along the string was stored in the key. As in the sentry box experiment, the kite was insulated, not earthed. By approaching a finger or knuckle, the experimenter could draw sparks,” Moura explained.

Like other eighteenth-century natural philosophers, Franklin thought of electricity as a fluid that built up and then discharged, flowing from one place to another. This fluid could be obtained in the laboratory by rubbing a glass tube with a piece of leather and stored in a Leyden jar, invented in the mid-century by Dutch scientists. The general idea behind the sentry box and kite experiments was to show that the fluid could also be drawn from the clouds. Franklin was fascinated by the physics of cloud electrification and other aspects of meteorology.

“In Franklin’s writings, there are no details showing whether he or someone else performed the experiment, but it does appear to have taken place. Another account of the experiment was produced 15 years later, in 1767, in a book by Joseph Priestley entitled The History and Present State of Electricity. Franklin helped Priestley obtain materials for the book and is therefore assumed to have agreed with its contents. Priestley’s account is far more detailed and includes participation in the experiment by Franklin’s son. However, it differs from the original 1752 account on several points,” Moura said.

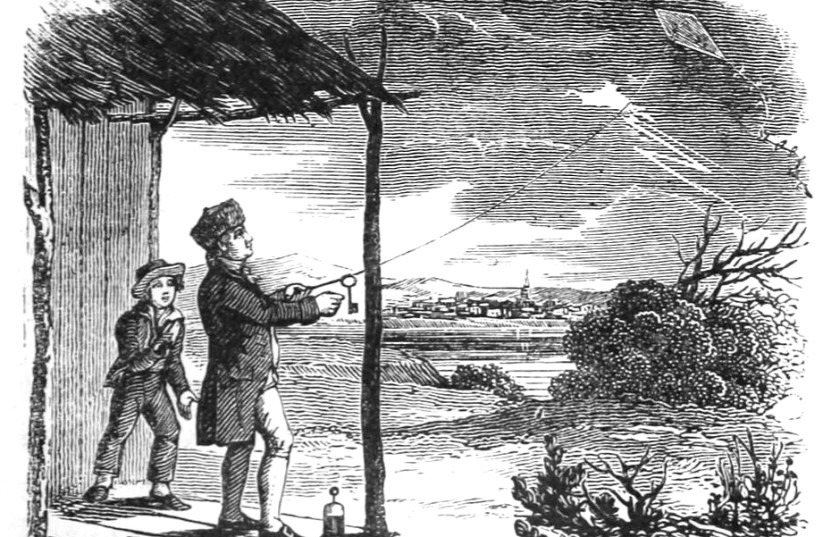

In his study of the illustrations depicting Franklin’s kite experiment, Moura argues that they were based on Priestley’s account. Many show Franklin with his son as a small boy even though at the time he was actually 21. Some also contain more important errors.

“Many show the experiment being performed in the open air even though Franklin specified that the experimenter must be in a ‘door or window, or under some cover, so that the silk ribbon may not be wet’, which would make it conductive. In most cases, the kite is being struck by lightning, or lightning bolts are very near it, although Franklin did not want to draw a lightning strike down upon himself. Most illustrations don’t show the silk ribbon that was meant to insulate the kite. Franklin simply holds the string. If that had been the case, he would have earthed the kite and ruined the experiment. One illustration shows Franklin holding the key near or on the string, which isn’t warranted by any account,” Moura said.

The illustrations should not be used indiscriminately, especially in science classes, he argued. They embody messages that can be construed in a confusing or wrong manner, both historically and scientifically, if they are not treated critically. As noted at the outset, the images stay in the mind of the viewer and any errors they foster are hard to eradicate.