For decades some 80,000 documents gifted by Albert Einstein upon his death in 1955 to the Hebrew University have been stored in a Jerusalem warehouse and gradually placed online in a digital archive format.

On Tuesday evening, after years of efforts, a groundbreaking ceremony at the university’s Givat Ram campus will be held for the Albert Einstein House – a museum that its founders think will quickly become a go-to destination for tourists and Israelis alike.

Nearly every adult in the developed world identifies the theoretical physicist and mathematician as one of the smartest persons in the modern era. Just his name is an adjective for the word “brilliant,” and Google records 330 billion mentions of him. But laymen are unlikely to be able to explain in a few sentences the basics of his theories of special relativity and general relativity which changed the world or even the meaning of his equation E = mc².

The Jewish, Zionist life of Albert Einstein, the world's most famous scientist

Most people are also probably ignorant of the fact that he was Jewish, a Zionist devotee and supporter of Israel decades before it became a state, and a co-founder of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, to which he bequeathed all his intellectual property and exclusive rights to his name, likeness, and personal and scientific writings.

After the Holocaust’s devastation was revealed, Einstein rejected numerous invitations and suggestions to return to Germany and to rejoin German scientific institutions. When he died in 1955, he left the documents to HU, which received them in the 1980s.

Theodor Herzl had a prophetic vision in 1902 that a Jewish state would be a hub of creativity and science. In 1918, scientist Chaim Weizmann – who would later become the first president of Israel – recruited Einstein to build a university in Jerusalem. Einstein, who is recognized as a father of HU, was its first honorary chairman of the board.

At the university’s 1923 inaugural ceremony on Jerusalem’s Mount Scopus, Einstein said: “I consider this the greatest day of my life.... Today I have been made happy by the sight of the Jewish people learning to recognize themselves and to make themselves recognized as a force in the world. This is a great age, the age of liberation of the Jewish soul, and it has been accomplished through the Zionist movement, so that no one in the world will be able to destroy it.”

Some fans of Einstein may not like, or may even be hostile to, Israel, but they could be drawn to this country by seeing visual material and reading and learning about the German-born genius.

The collections of documents about the man and genius scientist, family man and statesman were put online (http://www.albert-einstein.org) in 2012 in an expanded format to mark the 133rd anniversary of his birth. Although a relatively bare-bones digital archive had been established in Jerusalem in 2003, the new one is much more comprehensive, containing thousands of facsimile pages in the form of PDF files, images and translations which will continue to grow as more is processed and translated.

Physically located adjacent to the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem’s Givat Ram, the documents have been accessed electronically by many people, mostly professionals and scientists. Yet, although the texts from the Einstein Archives have been put online, the technical content is too abstruse for the nonexpert to understand and has for decades been kept out of public sight on the Edmund J. Safra Campus in Givat Ram.

LONGTIME FOREIGN MINISTRY official Ido Aharoni has been working since 2007 to establish the museum to promote Israel as an “attractive brand” to the world. Aharoni served in Israeli government positions for many years, including as the ministry’s consul for media and public affairs in New York.

“From 2007, I had frequently played with the idea of an Einstein museum as a way of promoting positive interest in Israel and the Jews, and tried to find partners that would make it happen,” he recalled. “In the summer of that year, I was appointed to serve as Israel’s first brand manager in Jerusalem. I wondered what I could tell about Israel that would inspire and interest people in Israel’s creative spirit. A global study showed that for this to happen, to attract more tourists, investors, positive media exposure and a better image, [it is essential] to associate Israel not just with hi-tech but with creativity and to humanize its persona.”

He held the position of brand manager until the summer of 2010, when he returned to New York, this time to serve as Israel’s consul-general. But the idea of an Einstein museum pervaded his thinking. “I presented the idea to the prime ministers, cabinet ministers, Jewish leaders and even then-president Shimon Peres, who was very interested, but nothing happened on the ground.”

He spoke to countless audiences in North America and Israel and finally aroused great interest from Friends of the Hebrew University in Canada, headed by Monette Malewski and Rami Kleinmann, who understood the potential and energetically carried the vision forward.

In a phone interview with Malewski from her home, the Canadian Friends chairman – who is about to step down but will attend the museum’s cornerstone ceremony in Jerusalem as part of the HU board meeting – said that “Einstein’s name is recognized and respected around the world. We had a project looking for a young ‘next Einstein,’ but we wanted a museum for him. There are only 300,000 Jews in Canada, so this was a major effort for us. We were the catalysts, and our board decided it was a good project. It will be an interactive museum, and not just a place to keep the documents.”

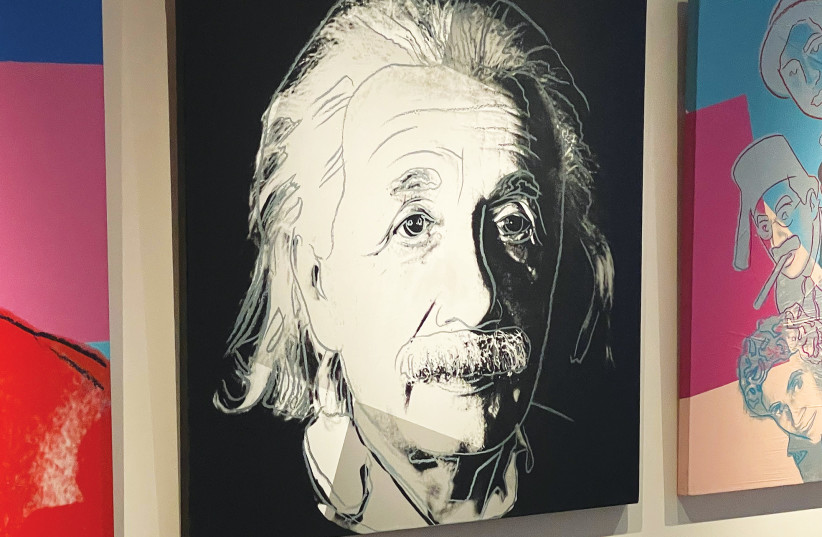

Aharoni left his government position in 2016 and formed a business partnership with Jose Mugrabi, a multimillionaire art collector and octogenarian who owns 5,000 pieces of original modern art, including 1,000 painted by Andy Warhol – one of Albert Einstein.

Warhol’s Albert Einstein 229 was created in 1980 and became a part of his Ten Portraits of Jews of the Twentieth Century series, which included a few of the most influential Jews in the 20th century. The artist became enthralled with a group of influential Jewish figures, including the theoretical physicist.

Mugrabi left Jerusalem for Colombia, where he made his fortune in textiles and then moved to New York.

In the fall of 2017, Aharoni told him of the idea. “Nothing really happened until one fateful meeting in New York with Jose. I asked representatives of the Canadian Friends in Toronto to come to meet with me and Mugrabi in New York. After learning about my vision for Israel as a brand and the role Einstein could play in it, he was not only quick to understand the importance of such an institution, but also immediately committed all the resources needed to make it happen.”

The art collector recognized the museum as a very important project and said he wants it to be his legacy. He was ready to underwrite the project, whose budget is NIS 64 million.

“We should be profoundly grateful to Mugrabi and the great people at the university and government that helped in realizing this dream,” said Aharoni.

Meeting with HU president Prof. Asher Cohen, Mugrabi and Aharoni agreed that an old, unused building on campus would be renovated and turned into the Marie and Jose Mugrabi Albert Einstein House.

“Mugrabi’s generous donation was the real game changer that triggered a national process, culminating with Israel’s government committing more funds for the museum,” Aharoni added.

The donor commissioned Daniel Libeskind – the famed Polish-American architect who moved with his parents to Kibbutz Gvat in the Jezreel Valley in 1957 and then to Tel Aviv, before moving to New York in 1959. He is best known for the Jewish Museum Berlin and for being the master plan architect for the reconstruction of the World Trade Center site in Lower Manhattan.

The groundbreaking ceremony of the Einstein museum will be held on the site on Tuesday, June 13, and the work is due to be completed by the end of 2024.

Prominent guests at the Tuesday ceremony are to include Mugrabi and his wife Marie, who have donated most of the NIS 64 million cost, Cohen, Aharoni, and representatives of Canadian Friends of HU who strongly backed the idea.

EINSTEIN WAS a man of this world, collaborating and exchanging ideas with friends and institutions and acting as a politically engaged citizen. For four decades, from 1914 until his death, he articulated his views on every issue on the agenda of mankind in the first half of the 20th century. In numerous articles, in correspondence with peers and in public lectures he expressed his opinions on a variety of public, political and moral issues, such as nationality and nationalism, war and peace, and human liberty and dignity. He also launched tireless attacks on any form of discrimination.

The contents of the museum will surely explain his basic theories, but it will do so in a comprehensible, visual way.

The general theory of relativity predicts that time progresses slower in a stronger gravitational field than in a weaker one. This phenomenon has to be taken into account in calculating the distances between a Global Positioning System (GPS) device and the satellites comprising the GPS system – so whenever we use GPS to find our exact location on Earth, we depend on general relativity.

General relativity describes the synthesis of the elementary particles of physics and of chemical elements in the early epochs after the “Big Bang” created the universe. It explains the processes involved in the formation of galaxies in more recent times. The theory also predicts that violently accelerated matter, like that of an exploding star, will generate waves of gravity, propagating at the speed of light and causing the space they traverse to shrink and expand alternatively. The detection of gravitational waves is one of the great challenges of astrophysical research, and could open a new window on the universe and enable us to trace its evolution almost to its beginning.

Cohen, a noted psychologist, told The Jerusalem Post in an interview that “we have been working on this huge project for over a year. Ido Bruno, who was director-general of the Israel Museum, is planning it. The 2,900-square-meter museum will be at the left, right inside the entrance of the campus, so that it will be very accessible to students, teenagers, visitors and tourists,” he said.

It will consist of one level underground and one above, Cohen continued. There will be no building like it in Jerusalem, made of high-quality materials – stone and glass – and designed by Libeskind, so that it will remain for generations to see. It will probably have a website, so that people who are interested in Einstein but can’t come to see it will be able to benefit, but the content has not yet been decided.

The government, through the Jerusalem Affairs and Heritage Ministry, has committed itself to allocating NIS 8m. for the design and content and NIS 14.5m. for the building, in addition to Mugrabi’s generous donation.

His wife, Marie, was born in Aleppo, but was taken by her parents to Milan and then to Brazil, where they met. They have been happily married since 1969. In an interview, Mugrabi said that the museum “means so much to us. My wife and our sons are extremely excited by the museum. It will be great for my country, encourage people to visit Israel and young people to learn more and maybe become another Einstein, who is a positive symbol of knowledge, Judaism and Zionism.”

This, he added, will be the only place in world where people will be able to learn so much about Einstein. “I never went to college; I was kicked out of 10 different schools.”

He knows Libeskind personally and admires him. He also regards Warhol as his “hero. I never met or talked to him; I only saw him from afar at a restaurant. But I regard him as having a huge influence on American art. He made some art on silk screen, which is what I used to do with my textile design. He had a great influence on American culture.”

And undoubtedly the Mugrabis’ museum, when it opens in a couple of years, will have a great, positive influence on Israel and its image.