Rare prehistoric flutes dated to 10,000 BCE, found in northern Israel's Hula valley, were made from bird bones and could imitate the calls of predatory birds.

This surprising find was published on Friday in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Scientific Report, providing rare direct evidence for sound-making instruments from the Paleolithic age .

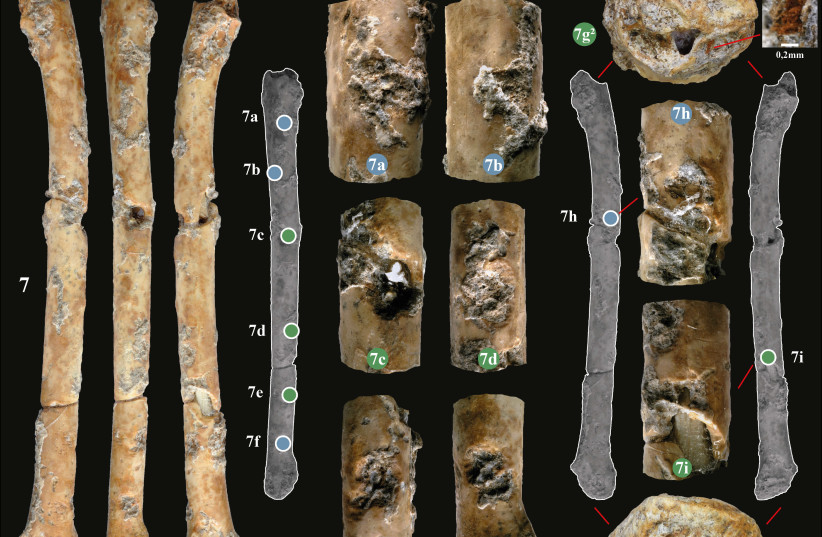

The seven perforated bird bones, called aerophones in the scientific literature, were found in the late Natufian site of Eynan-Mallaha, in the Hula Valley in northern Israel.

The scientists used a combined multidisciplinary approach to demonstrate that the flutes were intentionally made from bird bones over 12,000 years ago, in order to produce a range of sounds similar to raptor calls.

The use of the flutes remains unclear

At this point there can only be educated speculation as to the exact use and purpose of these extraordinary instruments, but the scientists suggested communication, attracting hunting prey and music-making, or some combination of these, as possible explanations.

"One of the vessels was found intact and as far as is known, in its state of preservation it is unique in the world," Dr. Lauren Davin and Dr. Hamudi Halaila said. "The copies prepared in its image made it possible to produce a sound which may have been played by the hunter-gatherers 12,000 years ago."

According to Dr. Halaila, "If the tool was indeed used for hunting, then this is the earliest evidence of sound production as a means of hunting. In most of the contemporaneous sites to Eynan, these vessels decay, but fortunately they were discovered by careful and gentle water filtration of the finds. This discovery provides important new data for ancient hunting methods, and joins the variety of prehistoric tools that characterize the beginning of the transition to agriculture and the domestication of plants and animals in the southern Levant."

Over 1,112 bird bones were found during excavations at Eynan-Mallaha, conducted from 1996 to 2005 by F. R. Valla and H. Khalaily. The site lies in the Basin of Hula Lake in the upper Jordan valley and is known for its rich Natufian deposits, covering most of the duration of this cultural period.

The Natufian archaeological culture, which in the Levant spanned about 15,000–11,700 before present, marks the transition from hunter-gatherer Palaeolithic societies into fully-fledged agricultural economies of the Neolithic.

Prof. Rivka Rabinowitz from the Hebrew University, where the research on the animal remains from the Eynan-Mallaha site is conducted, stated: "The current research indicates how important it is to preserve the cultural assets uncovered during the excavations, which continue to yield insights and new research directions on human culture, both with modern methods and collaborations between researchers from different disciplines."