About 12% of men around the world suffer from male infertility, which prevents them from siring a child. Couples facing such challenges can cope in only two ways: receive a sperm donation or adopt a child. Abnormalities in testis development and function lead to disorders of sex development and male infertility.

Infertility is defined as the failure to achieve a pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular unprotected sexual intercourse; male infertility accounts for about half of all cases. While male infertility is easily identified and classified into sub-groups, very little is known about the genetic and environmental mechanisms leading to male infertility.

Until now, no in-vitro system exists for modeling the testis. But in a world breakthrough, researchers at Bar-Ilan University (BIU) in Ramat Gan have developed organoids of the testis (testicles) that produce spermatozoa (the male gametes), synthesize testosterone (the main male sex hormone) and help regulate reproductive function. An organoid is a miniature and simplified version of an organ. An organoid is a miniaturized and simplified version of an organ produced in the lab in three dimensions that imitate the major structural, biological, and functional complexity of that organ.

Dr. Nitzan Gonen, a female researcher specializing in the process of fetal sex determination – together with research students Aviya Stopel, Cheli Lev, and Stav Dahari – said the artificial testicles will contribute to the advancement of research in male fertility and sexual development disorders and are expected to facilitate the eventual production of sperm in the laboratory.

They published their study in the International Journal of Biological Sciences under the title “Towards a ‘testis in a dish’: generation of mouse testicular organoids that recapitulate testis structure and expression profiles.”

A breakthrough in solving infertility

Their work could significantly advance understanding of the mechanisms involved in sex determination and provide solutions for male infertility.

The artificial testicles were produced in Gonen’s lab at BIU’s Goodman Faculty of Life Sciences and the Institute of Nanotechnology and Advanced Materials. The development of organoids has greatly advanced in the last decade with the realization that two-dimensional cellular samples in vitro cannot mimic the behavior of an entire organ. Today, organoids of the brain, kidneys, intestines, and other organs have already been produced. The testicular organoids created by Gonen’s group closely simulate a natural testicle.

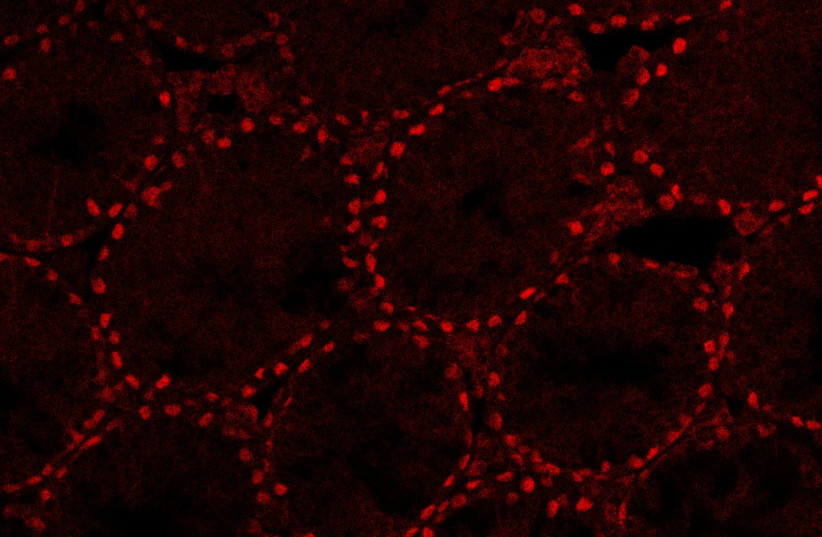

The artificial testicles were cultured from immature testicular cells sampled from neonatal mice. The research team realized the procedure was a success when they identified tubule-like structures and cellular organization highly resembling that of the in vivo testis. These tubular structures parallel the multiple seminiferous tubules present in the natural testicle, where the sperm is produced.

Growth of reproductive cells

The organoids were successfully cultured in vitro for nine weeks. This is considered a long period and can, theoretically, be enough time to complete the process of sperm production and hormone secretion. In mice, this takes 34 days, so the relatively long lifespan of the organoids may allow these processes to occur in vitro. Gonen said she doesn’t yet know if the existing model will produce sperm cells, but the members of her team have already noticed signs of the beginning of meiosis – a process in which gametes are produced. Gametes are reproductive cells, in this case, sperm cells with half the number of chromosomes as in a normal cell, that “wait” for the completion of the other half from another gamete, in this case, an egg, upon fertilization.

Organoids usually resemble organs in the embryonic stage. In this case, the researchers created conditions that allowed the organoid to mature in the laboratory and showed that even testicles grown from embryonic cells can develop and grow clear sperm tubes. They were not successful in their attempt to grow organoids from adult mice testis.

“Artificial testicles are a promising model for basic research on testicle development and function, which can be translated into therapeutic applications for disorders of sexual development and infertility,” explained Gonen.

She said the technique could eventually help infertile men, but not make it possible for lesbians to obtain a fetus with the genes of each of them to make a baby.

In the future, Gonen plans to produce organoids using human samples. A testis produced from human cells, for example, could help children being treated for cancer, which may impair their ability to produce functional sperm. As children are too young to produce their sperm, these samples can be frozen and used in the future to have children. Gonen’s vision is to grow testes organoids from biopsies of children with cancer and hopefully grow fertile sperm in vitro.