Bookworms who love to read every volume they can their hands on are admirable, but those greyish creepy crawlers called silverfish and others that suddenly pop out of old books are no pleasure. What attracts them and what do they eat?

Now, American researchers who have published in the American Chemical Society’s Journal of Proteome Research under the title “Wheat-Based Glues in Conservation and Cultural Heritage: (Dis)solving the Proteome of Flour and Starch Pastes and Their Adhering Properties” believe they have uncovered the secret.

Wheat-based glues made from wheat flour or starch and water have been used as far back as ancient Egypt. The earliest use of wheat paste may have occurred with the manufacture of papyrus, as documented in 77 CE by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History, Book VIII, which contains important details regarding the treatment Egyptians performed on wheat flour to extract the starch using boiling, straining, and diluted vinegar, and its application.

How does it work?

But little is known about their protein makeup. Flour glues are made from the insides of wheat grains that includes the gluten that’s so scrumptious to bookworms and microorganisms alike but can cause celiac disease in humans.

Flour is very sticky when wet, and it hardens upon drying. This effect is worse in wheat-flour-based glue than starch-based glue because of the gluten proteins. Today, wheat starch paste is the most commonly used adhesive for repairs by book and paper conservators whose repairs include hinging, mending, lining, facing, reinforcement, consolidation, or as a fixing media.

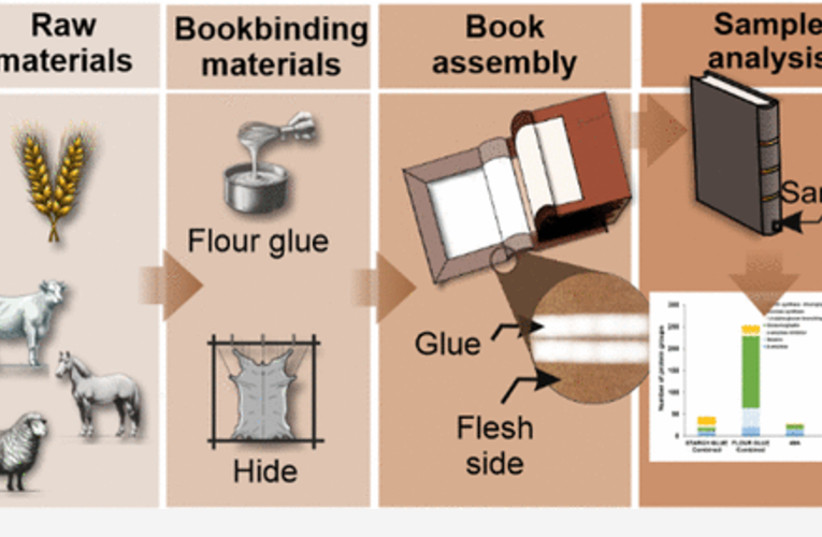

Starch glue, on the other hand, is made from the proteins that remain after most of that gluten is removed, making it less attractive to pests. The researchers have analyzed the proteins in wheat-based glues applied in historic bookbinding to provide insights on their adhesiveness and how they degrade. This information could help conservators restore and preserve treasured tomes for future generations.

Understanding the nature of the proteins in these glues and how they affect the adhesives would help book conservators choose the best approaches and materials for their work. So, Dr. Rocio Prisby of George Mason University in Virginia and colleagues created protein profiles for both flour and starch glues, identified differences among them, and used this information to analyze books from the US National Library of Medicine archives.

To create the protein profiles, called proteomes, the researchers first extracted proteins from lab-made versions of flour and starch glues. Then, they used mass spectrometry data and bioinformatics software to identify the types and relative abundance of proteins in the samples. The team discovered that flour glue has more proteins and a wider variety of them than starch glue. In addition, the proteins in starch glue were particularly durable and flexible, making it a potentially better choice than flour glue for book repairs.

The researchers then used their protein profiles to analyze historic book binding samples from the archives and confirmed that the adhesives were flour-based because of their gluten content and identified degraded gluten in the samples, which could indicate damage and a loss of stickiness. They also identified that the chemical breakdown of leather and glue in a book’s cover impact each other, possibly leading to faster overall deterioration.