Sidney Reilly – the latest subject in the Yale University Press biography series called Jewish Lives – was born Shlomo Rosenblum in Odesa or Kherson or Bendzin or Pruzhany in either 1872 or 1874. He also seems to have convinced British Intelligence that he was an Irishman, born in Clonmel.

The subject of countless books and a television series during the 1980s, he remains an almost fictional, yet romanticized figure lost in the mists of times.

Reilly, apparently an inspiration for Ian Fleming’s James Bond, was a multilingual entrepreneur, dissolute conman and insubordinate servant of Britain’s MI6 intelligence service.

The author of Sidney Reilly: Master Spy, Benny Morris, one of Israel’s leading historians, has attempted to reclaim the real Reilly a century after his killing by the forerunner of today’s FSB (Federal Security Service). Undaunted by the fact that Reilly always lived in the shadows, leaving few traces, Morris has applied his tremendous expertise to research the enigma of who was Sidney George Reilly.

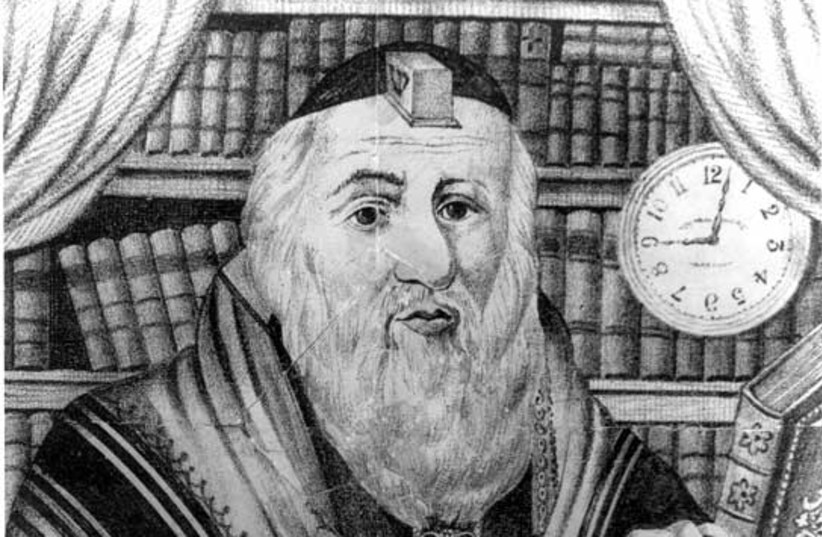

Reilly seems to have repressed his Jewishness, but Morris believes that he may have descended from the Vilna Gaon and was related to Leon Trotsky.

Reilly was a man for all seasons. He worked for czarist intelligence, the Okhrana, as well as for Scotland Yard’s Special Branch. Settling in Lambeth, London, probably on a spying mission, he joined the Royal Institute of Chemistry and set up his own company to sell “Tibetan remedies” to the gullible – the equivalent of a snake oil salesman of American lore.

Reilly was the womanizer’s womanizer – a girl on every page in this book – and was married three or four times, often at the same time.

Reilly ran all the operations of his old friend, Jewish benefactor Moisei Ginsburg, at Port Arthur. Morris surmises that Reilly may have passed on information to the Japanese in their war with Russia and thereby brought about their attack on the Russian fleet at Port Arthur in February 1904.

WORLD WAR I brought new pickings for Reilly as an arms purchaser for Russia in New York, and he projected the persona of an Englishman, loyal to crown and country. He joined the Royal Flying Corps, entered Russia in 1917 and was attached to the British military mission at Arkhangelsk. This was the fateful year of revolutions. Sporting a British military uniform, Reilly was cultivating the Bolsheviks while simultaneously attempting to keep Russia in the war against the Kaiser’s Germany.

Plotting the downfall of the new regime of Lenin and Trotsky, he hoped that Latvian forces would arrest the Soviet leadership at the All-Russia Congress of Soviets at the Bolshoi Theatre. Like many actions during the following decade, it came to nothing. After Dora Kaplan’s attempt to assassinate Lenin, the Red Terror was unleashed, the British Embassy was raided and much of Reilly’s network in Moscow was dismantled. Reilly managed to escape to London, but he was sentenced to death in absentia.

He managed to return to Russia shortly afterwards and began to send back reports to British Intelligence on the civil war between Reds and Whites. He reported on the starvation of multitudes and the bestialities carried out in the name of ideology. Tens of thousands of Jews were slaughtered, mainly by the Whites, but Reilly seemed indifferent to such suffering. Only in March 1919 did he mention a pogrom in a report back to London.

During this period, he was able to meet figures such as Churchill and Henry Wickham Steed, later editor of The Times and endorser of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

Morris notes that Reilly met Pinhas Rutenberg, former social revolutionary, friend of Jabotinsky and instigator of the electrification of the Yishuv – and they probably discussed Zionism and a possible future Jewish state.

Reilly was an admirer of another social revolutionary, Boris Savinkov, whose Napoleonic stature convinced Reilly that he was the man to overthrow Bolshevism and lead the new Russia. The early 1920s was a time when the Bolsheviks had entrenched themselves, and thus many former opponents turned coat in recognizing this new reality. Savinkov was persuaded to return to Russia in 1924 by “friends,” arrested and pledged loyalty to the Bolsheviks in return for his life. He was found a few weeks later, seemingly having “jumped” from his fourth-floor prison window.

Reilly, appalled by Savinkov’s capitulation and obsessed with overthrowing the Bolsheviks, remarkably repeated the same mistake in returning. Immediately arrested, he portrayed himself as “an Englishman and a Christian” during interrogation – yet Putin’s predecessors knew exactly who he was. He met his death by bullets in the back a few weeks later.

Benny Morris has done a brilliant job under difficult circumstances in attempting to reconstruct the life and times of Sidney George Reilly – the mystery man of espionage and also a poor Jewish boy from the shtetl.■

Sidney Reilly: Master Spy

By Benny Morris

Yale University Press

Pages 196; $26