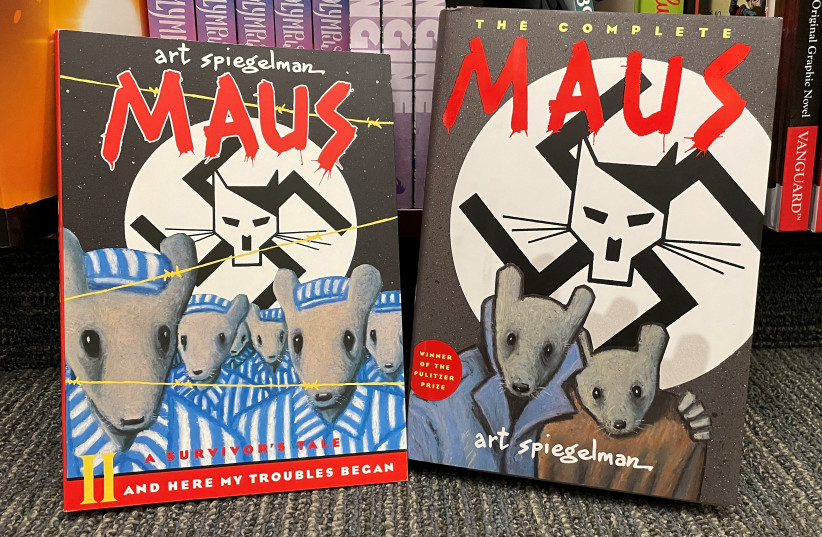

A Missouri school board has decided not to ban “Maus,” the graphic memoir about the Holocaust, after considering doing so because of a new law barring the distribution of “explicit sexual material” in schools.

The board of Nixa Public Schools voted unanimously on Tuesday night to retain Art Spiegelman’s award-winning book in local schools.

It voted to remove or restrict six other books. Two — a graphic version of Margaret Atwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale” and “Blankets,” a graphic memoir about leaving Christianity — were removed out of concern that they violated the law, which prescribes penalties for distributing sexually explicit material to students. The board also voted to remove two books in response to parent challenges, and to make two others available at parent request only.

“The board wanted to review anything that might violate the new law to offer protection to staff if they decided to keep it, since there is a criminal offense aspect to the law,” Zac Rentz, a district spokesperson, told the Jewish Telegraphic Agency by email on Wednesday. “The difference between those books would be they felt Maus didn’t violate the law and that the other books did.”

Was the attempt to remove Maus antisemitic?

Rentz had previously told JTA that the board’s decision to review “Maus” for sexual content “should not be viewed as an attempt to limit students’ access to information about the Holocaust or be viewed as antisemitic.”

Twenty-eight people spoke during the three-hour meeting Tuesday night, according to local news reports. Some argued in favor of keeping the books while others argued that children would be at risk if they were to encounter the material in their school libraries.

Spiegelman’s book was an early, visible casualty of the nationwide conservative-led movement to remove or restrict books from school libraries for perceived inappropriate content when a Tennessee district voted to remove “Maus” from its middle school curriculum last year. There, school board members cited profanity in the book and a drawing of a naked mouse, which represented the author’s mother after she died by suicide.

Spiegelman worked with the literary free-speech advocacy group PEN America to lobby the Nixa board to retain his books and others that were on the chopping block. The book-banning movement has taken aim most squarely at books with LGBTQ+ content or books about racial equity, though Holocaust books and other books with Jewish content have been caught in the dragnet.

The price of banning books

“We haven’t learned much from the past, but there’s some things you should be able to figure out,” Spiegelman said in an interview with the group. “Book burning leads to people burning. So it’s something that needs to be fought against.”

On Wednesday, PEN America criticized the Nixa board’s decision to remove or restrict books. “While Maus will thankfully remain on bookshelves, there is no reasonable basis for blocking student access to the other six books,” Kasey Meehan, PEN America’s Freedom to Read program director, said in a statement. “These new bans are an unfortunate – and predictable – outcome of legislation intentionally designed to suppress certain ideas.”

Some other Missouri school districts have interpreted the state’s new law barring the distribution of “explicit sexual material” to mean that comic books and graphic novels, in particular, could expose staff to legal liability. One district near St. Louis ordered staff to temporarily pull not only “Maus,” but also hundreds of other illustrated books, including several Holocaust history books for young readers.