Scientists at Cedars-Sinai have mapped the cellular changes linked to endometriosis to help improve therapeutic options for the millions of women affected by the disease.

The study was published Monday in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Genetics.

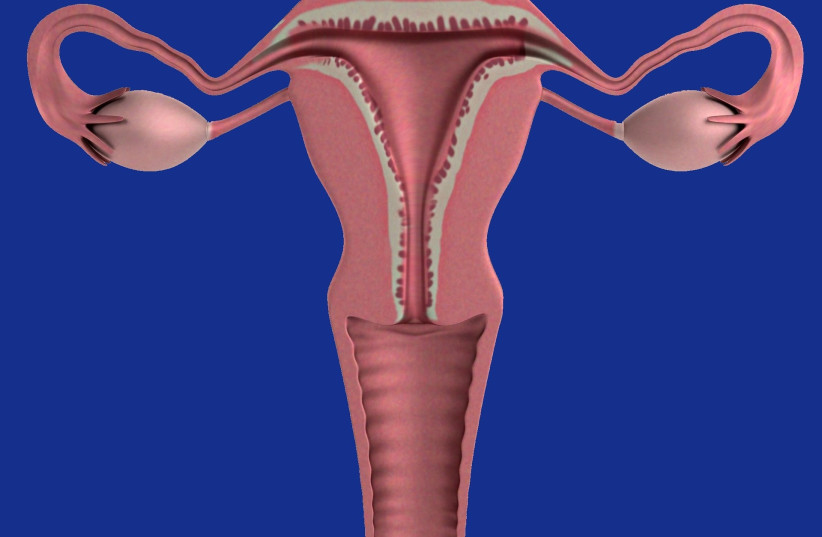

About 1 in 10 women are plagued by the condition, which occurs when cells similar to those lining the uterus grow elsewhere in the body – most commonly on the ovaries, fallopian tubes and in the abdominal cavity. Patients with the disorder can experience chronic pain, infertility, headaches and fatigue, as well as bowel and bladder dysfunction.

Despite it being so common, it takes an average of seven to eight years to be diagnosed with endometriosis because it is so little is understood about it. Neglecting the disease could also be deadly according to a study last year that found women with endometriosis also carry a slightly increased risk of epithelial ovarian cancer.

“Endometriosis has been an understudied disease in part because of limited cellular data that has hindered the development of effective treatments. In this study we applied a new technology called single-cell genomics, which allowed us to profile the many different cell types contributing to the disease,” said Kate Lawrenson, PhD, an associate professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Cedars-Sinai, and co-senior and corresponding author of the study. “The disease can travel throughout the body, so in many ways, it behaves like cancer. But why does endometriosis behave like cancer while rarely becoming cancer?”

To better understand the disease, Lawrenson and her colleagues mapped molecular changes by examining more than 400,000 cells from 21 patients, some of whom had endometriosis and others who did not.

“Endometriosis has been an understudied disease in part because of limited cellular data that has hindered the development of effective treatments. In this study we applied a new technology called single-cell genomics,which allowed us to profile the many different cell types contributing to the disease."

Kate Lawrenson

“Large-scale next-generation sequencing projects have been incredibly helpful in understanding how cancer works and in designing targeted therapeutics. We expect it can do the same for endometriosis,” said Lawrenson.

“We were able to identify the molecular differences between the major subtypes of endometriosis, including peritoneal disease [affecting the abdominal cavity] and ovarian endometrioma. This resource can now be used by researchers all throughout the world to study specific cell types that they specialize in, which will hopefully lead to more efficient and effective diagnosis and treatment for endometriosis patients. It really is a game-changer.”

What relief is currently available for endometriosis?

Currently, there are few treatment options for endometriosis, mainly surgical removal of cysts and lesions, pain relief, and hormone therapies, such as the contraceptive pill or intrauterine system (IUS).

In severe cases, women may resort to having their ovaries or uterus removed. Researchers expressed hope that in better understanding the molecular underpinnings of the disease they will be able to develop more targeted therapies, as has been done for cancer.