Scientists have successfully prevented the symptoms of the rare genetic disorder Robinow Syndrome, which affects the growth and development of the skeletal system, causing patients with the disease, and others similar to it, to have short-limb dwarfism and facial abnormalities.

In a new peer-reviewed study published by the Company of Biologists in the Development journal on Wednesday, researchers at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Ohio and the Van Andel Research Institute in Michigan showed that the use of a drug can restore the length of limbs affected by FZD2-associated autosomal dominant Robinow Syndrome in mice.

Findings may help researchers develop treatments for other skeletal diseases

“The idea of treating the limb bones medically rather than surgically is a really important proof of principle, which we demonstrate in this study.”

Lead study author Rolf Stottmann

The research provides hope for the development of therapies to treat similar skeletal diseases.

Although autosomal dominant Robinow Syndrome disorders only occur in about 50 families in the world, they are linked to genetic mutations that can either be inherited from a parent or develop spontaneously, making diagnosis easier.

“We began the project by studying the genomes of families with structural birth differences of the brain and face who had not yet received a genetic diagnosis,” said lead study author Rolf Stottmann. “We identified that one of the initial families in this cohort had a mutation in the FZD2 gene.”

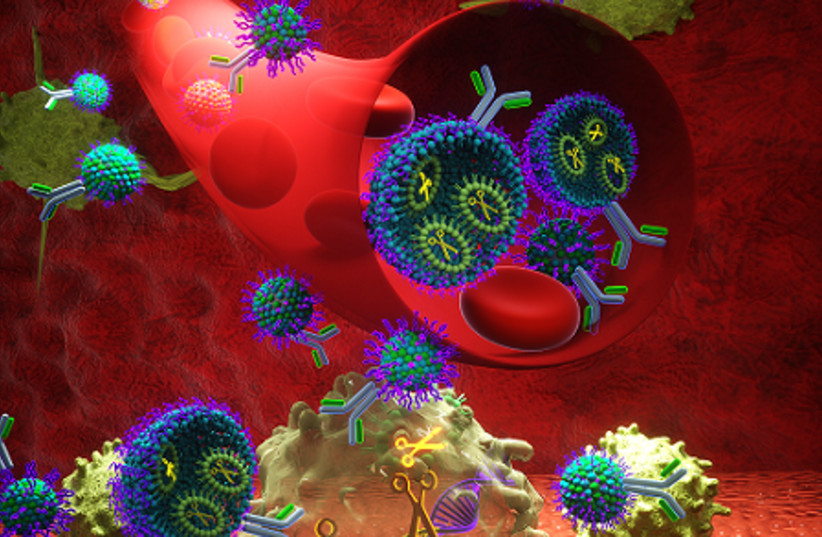

FZD2, a gene that has been linked to autosomal dominant Robinow Syndrome, produces a protein involved in sending signals that cells use to organize themselves into tissues.

The researchers used CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing to cause mutations in a specific part of the gene, recreating the types of mutations found in humans with the disease.

The researchers predicted that mutations that cause facial and skeletal facial and skeletal malformations disrupt signaling and skeletal growth. They therefore treated pregnant mice with a drug that stimulates the signaling pathway.

“This drug is an attractive option because we think we know how it works and previous work had shown that it could rescue cleft palates in a mouse model,” Stottmann said.

The team found that mice treated with the drug had significantly longer limbs than untreated mice. The success of the mouse trial suggests the drug could eventually be used to treat humans.

“The idea of treating the limb bones medically rather than surgically is a really important proof of principle, which we demonstrate in this study,” said Professor Stottmann, “we are very excited to test if this could work in the context of other genes associated with autosomal dominant Robinow Syndrome.”

“Overall, this study demonstrates an essential role for the signaling functions of the C-terminal region of FZD2 and validates the findings of FZD2-associated AD-RS we previously observed in humans,” the study read.