Egyptian voices are calling for the return of the Rosetta Stone, the key to deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs, among the most important artifacts in the British Museum, to its place of origin.

This could spur many more such cases, as experts expect there to be increasing calls on Western museums to give back artifacts that were taken centuries ago from places such as Egypt during the colonial era.

As the British Museum marks the 200-year anniversary of unlocking hieroglyphs using the Rosetta Stone by hosting a major exhibition, Egyptologist Dr. Monica Hanna, dean at the Arab Academy for Science, Technology & Maritime Transport, organized a petition calling on the museum to return the stone to Egypt, arguing that the artifact was acquired illegally.

What is the Rosetta Stone?

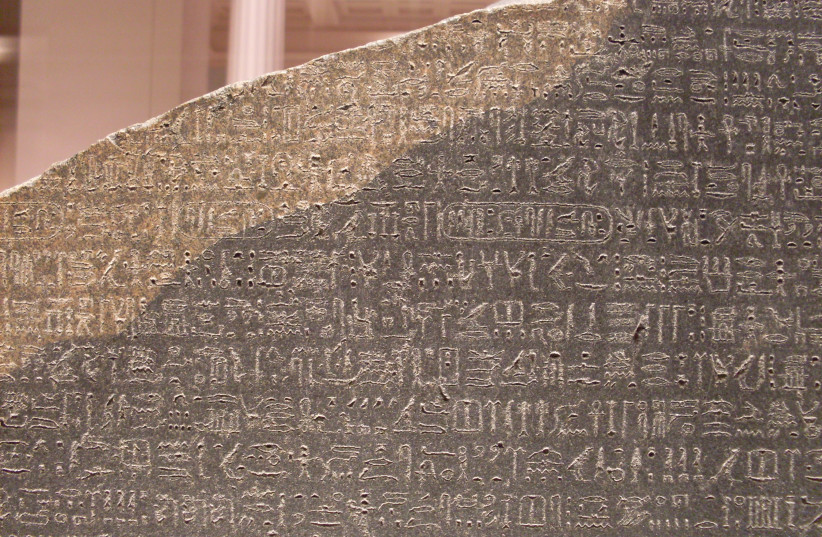

The Rosetta Stone is an ancient stele that contains a decree documenting the coronation of Ptolemy V as the pharaoh of Memphis in 196 BCE. The decree is written on the stone three times, in ancient Greek, the administrative language of the time; and in ancient Egyptian, the day-to-day language, using both hieroglyphics and the demotic script.

With the Rosetta Stone's discovery by the French in 1799 during the Napoleonic conquest of Egypt, and its acquisition by the British Empire after defeating the French in a battle for Egypt, the artifact became the first known translation of hieroglyphics to another language. This led to the first decryption of hieroglyphics, a form of writing that stopped being used in the 4th century CE.

Dr. Sherine El Taraboulsi-McCarthy, a former visiting fellow studying politics at Keble College at the University of Oxford, told The Media Line that the Rosetta Stone has been on display in the British Museum since 1802 with only one break during World War I.

She adds that the return of such artifacts to their countries of origin is, indeed, a growing question for Western museums, given that the current geopolitical situation, and the global perception of history, is shifting.

"I think it is becoming more of a challenge [for the museums] and, quite simply, this is because the times have changed," she said.

Raising awareness

El Taraboulsi-McCarthy believes that while the world is becoming increasingly multipolar, there is more awareness of history in postcolonial states, adding that social media has played a key role in amplifying and connecting those voices.

"I see that calls for reparations are becoming louder and more impactful," she noted.

There has been no formal request from the Egyptian government to the British Museum for the return of the Rosetta Stone to Egypt, a museum spokesperson told The Media Line.

The spokesperson added that, since the discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799, 28 similar decrees have been found in the same area of Egypt. "The majority of these decrees, 21, remain in Egypt," he said.

The other copies of the decree helped scholars to understand the full hieroglyphic text, which is only partially preserved in the Rosetta Stone, according to the museum spokesperson. He adds that the British Museum "greatly values positive collaborations with colleagues across Egypt."

He cites as an example of such collaboration a European Union-supported project called "Transforming the Ancient Egyptian Museum in Cairo (2019-2022)." As part of that project, "the most impressive stela inscribed with the decree text was redisplayed near the entrance to the museum in Cairo earlier this year," he said.

Dr. Doga Ozturk, a historian of late Ottoman Egypt, and an analyst and writer focusing on Turkey and the Middle East, told The Media Line that the 200-year anniversary of the deciphering of hieroglyphs provides a good time for Egyptians to get international attention for its causes.

He adds that, on a broader scale, the fact that a number of artifacts have been returned recently to their places of origin by Western museums creates momentum for this Egyptian request.

Dr. Gabriel Polley, a historian of British involvement in the Eastern Mediterranean in the 19th century who holds a doctorate in Palestine studies from the University of Exeter, told The Media Line that this trend will probably continue to expand in the coming years.

"The next decade is going to be dominated by calls for the repatriation of objects from all parts of the global south, supported by campaigns led by diaspora communities and their allies for the decolonization of these spaces," he says.

As these calls grow louder, he adds, "all museums with such collections will have to consider how they respond."

Ozturk says that to address the issue as a whole, every case must be analyzed individually.

"The question of repatriation of objects should be discussed on a case-by-case basis, since coming up with an overarching principle would probably be simply impossible, and would just block the whole issue from moving forward in a constructive manner," he added.

Public access and discussion

Additionally, he believes that the discussion should not be limited to academic circles and should be broadened to include all relevant parties and the general public.

"People who are visiting these museums should learn about how these objects actually ended up in these museums for them to look at," he said.