It was Sunday January 2, the first day of a new year in which we might pray for good health. Odd and difficult to understand, we don’t pray for overall good health on Shabbat in the prayer services. However, we do include the Jewish names of individuals who are ill with their mother’s Jewish name in a blessing, which is perhaps referring in large part only to the Jewish people on a national level, which is recited during the Torah reading portion of the morning service.

Anyway, as I looked out at the distance, maybe into the abyss, from an Orthodox siddur I recited the weekday, routinized, prayer for God to heal us – blessing God, I quote here, “Who heals the sick of the people of Israel.” Happily, the prayer is communal: Refaeinu, heal us (again, intending in context to the Jewish people, not “me” individually). Still, at a time of the year that one might make New Year’s resolutions, it got me to thinking.

Honestly, one wouldn’t have expected us to pray for the health of the Egyptians during the time of Pharaoh, nor the German people in the days of the Holocaust. We would have perceived both of those peoples – not just their leaders – as enemies, whether or not each of them truly warranted being painted with the broad brush inherent in that way of thinking. Who, after all, would be expected to pray for the health of an enemy nation?

Yet today, still driven by a somewhat rock-solid prayer regimen, many in the Orthodox tradition blithely pray, in effect, that God heals the Jewish people, almost as if the rest of the world is somewhat irrelevant. That is, as if God would want us to ask solely for His intercession in the affairs of the Jewish people and not in the affairs of others.

Legendarily, all the rest of the nations of the world rejected the Torah, and when God ultimately offered it to the Hebrews, we accepted it at the foothills of Sinai. That thought process makes some observances cavalierly oblivious in a world that is overwhelmingly gentile. As if God might only exclusively care for His nation! Parenthetically and in fairness, many of us have the world at large in our thoughts when we pray to God, but that’s not the verbiage of the Orthodox liturgy.

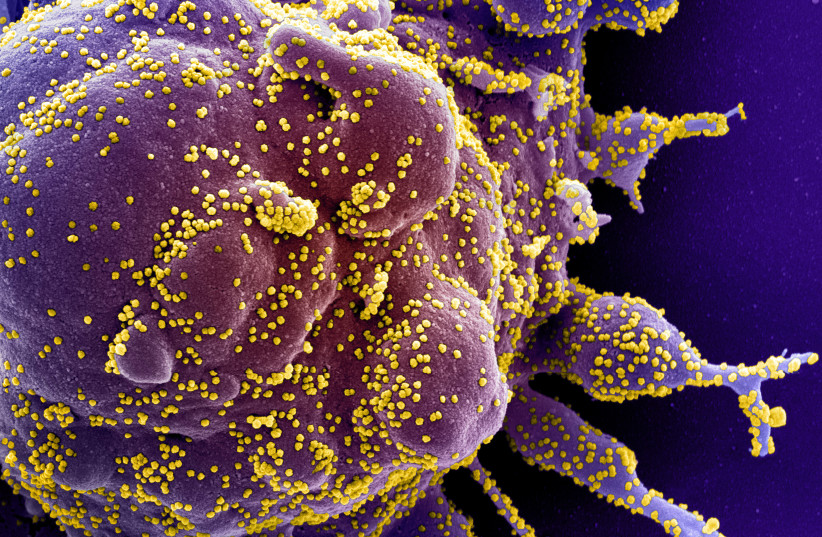

If we didn’t appreciate it before, the last two years have unquestionably proven the interconnectivity of everyone in the world, underscoring the nation-to-nation interrelationship of the health of everyone on the planet. The origin of the pandemic was in Wuhan, China, whose demographic is hardly Jewish.

What is the meaning of all of this for us? Simple. If only for self-absorbed reasons, shouldn’t we, as a people, have urgently wanted and want good health for all the people of the world, no matter who they are? Wouldn’t the house of Israel be better protected if the people of the world are more resistant to the virus? More specifically, if we believe with conviction in the efficacy of our prayers – or, the whole idea of prayer itself – shouldn’t all of us have prayed, particularly at the end of 2019, that God heals all the people of the world?

For example, perhaps prayers asking for God to heal us were composed when the Jewish people believed – and for good reason – the rest of the world was oppositional to us, when much of our prayerful relationship with God was significantly about His watching over us in a dark, dank, antisemitism-steeped world. Ergo, the prayers to heal us, redeem us, gather us, hear our voices, be favorable to us, and finally, to establish peace, goodness, blessing, graciousness, kindness and compassion toward us. (See the Orthodox Shemoneh Esrei.)

That said, especially nowadays, we should want our prayers – particularly about health and welfare – to be explicitly expressed universally to all human kind, directly urging God to make the world a better place. If the rest of the world becomes largely immune to Omicron, don’t we all – including the Jewish people – benefit from it?

This may sound to many like the thinking of someone audacious enough to preach, but despite centuries of how traditional prayer has been offered, how to pray to God, how to pray for the health of some who might even think to do us harm, the world has evolved. Accordingly, we may need to reconsider how we ask God to continue to repair it. Depending on the prayer book used in some of their synagogues, the Conservative and Reform movements offer far more accommodating prayers employing different phraseologies. Typically, they seek God’s healing power without an unwarranted jingoism – changing the customary wording of the prayer for healing to beckoning God “who heals the sick” (rofeh cholim) - anyone who is sick.

Perhaps it’s time for a few meaningful New Year’s resolutions. Have a happy, healthy New Year and godspeed.

The writer, a frequent author, practices white collar criminal defense law at Stroock & Stroock & Lavan in New York, and is the author of Moses: A Memoir (Paulist Press, 2003).