Black September will forever be associated with the massacre of Israeli athletes at the 1972 Munich Olympic Games.

But the name of the terrorist group responsible for that atrocity stems from a Palestinian defeat two years earlier, one that impacted Israel and the Middle East, and even elevated Cold War tensions between the Soviet Union and the United States.

The Munich Olympics were planned to showcase the new postwar democratic West Germany (the previous games on German soil – the 1936 Berlin Olympics – had been hosted by Adolf Hitler). But the Bonn government’s hopes to present to the world a very different Germany were to be stymied.

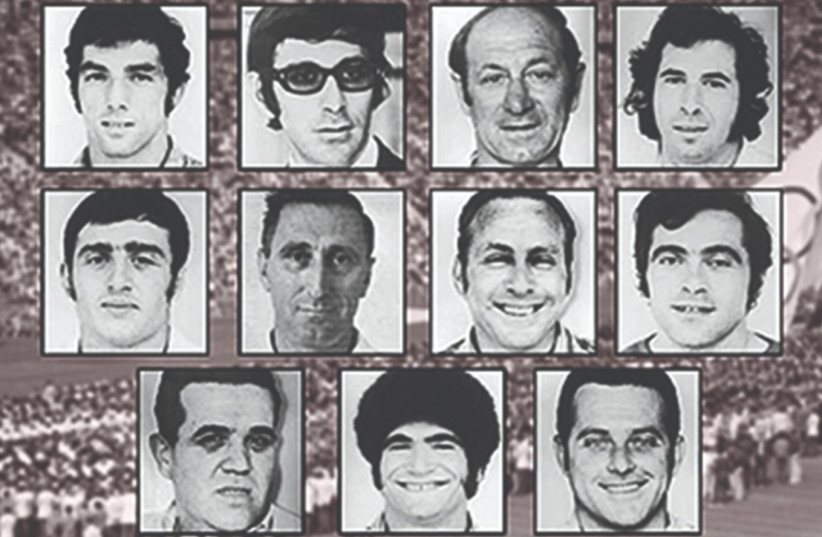

Before dawn on September 5, eight Palestinians from the Black September organization, established in 1971 as the elite strike force of Yasser Arafat’s Fatah movement, scaled the fence surrounding the Olympic Village. Disguised as athletes and using stolen keys, they forced their way into the quarters of Israel’s Olympic team, initiating a 20-hour hostage saga that ended with a botched German attempt to free the hostages and 11 Israeli athletes dead – nine of them murdered while bound and gagged.

The “Munich Massacre” played out in full view of the assembled international media. Even though the coverage depicted the terrorists’ bloodthirsty behavior, it nonetheless helped propel the Palestinian issue to the forefront of the global agenda.

Ironically, the name “Black September” did not originate from an event associated with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, but rather from the intra-Arab confrontation that erupted in Jordan in September 1970.

In the aftermath of the 1967 Six Day War, Jordan – now smaller in size with the loss of Jerusalem’s Old City and the West Bank – became the primary base from which Palestinian fedayeen struck against “the Zionist entity.” Israeli communities along the border lived in constant fear of a terrorist infiltration or Katyusha rocket fire.

My wife grew up in one such frontier community – Kibbutz Tel Katzir in the Jordan Valley. As a baby, she was continually rushed by her mother to the children’s bomb shelter whenever the security situation demanded.

These fedayeen attacks generated IDF reprisal raids, which in turn heightened the risk of a larger Israel-Jordan confrontation.

BUT IT wasn’t just Israelis whom the armed Palestinian groups were threatening. The fedayeen acted in Jordan as a state within a state, independent from the Hashemite government and challenging its authority.

Radical Palestinians called for the overthrow of the “reactionary” Jordanian monarchy, declaring the kingdom an illegitimate creation of British imperialism in what was part of historic Palestine. Amid the soaring violence, there were two separate assassination attempts against Jordan’s King Hussein.

Matters were to spiral out of control when, on September 6, 1970, the Marxist “Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine” (PFLP) hijacked Western airliners to the Dawson’s Field airstrip near the city of Zarqa. Ultimately, a TWA Boeing 707, a BOAC VC10, and a Swissair DC-8 were all forced to land at the PFLP’s self-proclaimed “Revolutionary Airport.”

The September 11 attacks

On September 11, most of the 310 passenger-hostages from the three aircraft were transferred to Amman and released, but the PFLP refused to free the flight crews and 56 Jewish captives. (At the end of the month they were exchanged for prisoners held in European jails.)

On September 12, the PFLP blew up the three aircraft, producing dramatic images that appeared on the front pages of newspapers worldwide.

This incident was the final straw for the embattled Jordanian monarch. He declared martial law on September 16 and sent his army to confront Palestinian strongholds across his kingdom the following day.

Then the domestic Jordanian crisis escalated into a Cold War emergency. On September 18, more than 300 Soviet-supplied Syrian tanks, specially marked with Palestinian insignia, invaded Jordan from the North in support of the insurgents. This, while in eastern Jordan, an Iraqi armored division was stationed, having been there since the Six Day War.

Syria and Iraq were Soviet allies, while Jordan was solidly in the Western camp. Washington could not sit idly by as a key Arab partner succumbed to a hostile takeover.

In response to King Hussein’s urgent appeals for help, Washington beefed up the Sixth Fleet’s presence in the eastern Mediterranean. But while the US flexed its muscles, it was preoccupied with the Vietnam War.

Unenthusiastic about being sucked into an additional military intervention, the Nixon administration turned to Israel for assistance. Golda Meir’s government agreed to help, but not before receiving an American commitment to protect it from a possible Soviet counterstrike.

The IDF mobilized on the Golan Heights as if ready to move against Syria, and the Israel Air Force flew menacingly over the Syrian armor columns in Jordan.

Damascus got the message, as did Baghdad. On September 22, the Syrians started to withdraw from Jordan, while the Iraqis remained passive. Without outside intervention on behalf of the insurgents, the Jordanian army decisively defeated the fedayeen. (Arafat was to make the exaggerated claim that Hussein’s forces killed 25,000 Palestinians.)

The 1970 Black September crisis became an inflection point in Israel-US ties. Israel demonstrated that it could augment American power in the Middle East. If Washington had once felt a moral obligation to assist a sister democracy, it now saw Israel as a strategic asset, with the relationship upgraded into a de facto (and later a de jure) military alliance.

Encapsulating this shift, senator Jesse Helms, a conservative Republican who was initially lukewarm on Israel, was to coin the phrase that the Jewish state is “America’s aircraft carrier in the Middle East.”

POSTSCRIPT: WHILE Israel’s civilian and military leadership supported helping King Hussein defeat his enemies, there were dissenting voices.

Perhaps most prominent among them was IDF general Ariel Sharon – later Israel’s prime minister (2001-2006). Then head of the Southern Command, Sharon saw strategic advantage for Israel if the Palestinians achieved statehood in the East Bank, where they were a demographic majority, believing that such a development could help facilitate an Israeli-Palestinian arrangement over the West Bank.

Quite naturally, the Jordanian leadership abhorred his “Jordan is Palestine” approach. But the realities created by Jordan’s 1994 peace treaty with Israel necessitated letting bygones be bygones, and Amman’s antipathy toward Sharon over his Black September position was to wane.

In the late 1990s, as minister of national infrastructure and minister of foreign affairs in Benjamin Netanyahu’s first government, Sharon forged close working relations with the Jordanians. Importantly for them, he facilitated the transfer of hundreds of millions of cubic meters of water to their arid kingdom.

The writer, formerly an adviser to the prime minister, is chair of the Abba Eban Institute for Diplomacy at Reichman University. Connect with him on LinkedIn, @Ambassador Mark Regev.