We’ve all seen that person. The one who feels unwell at a concert or a public event. As he or she lies on the ground, a crowd of gawkers assembles. Eventually a doctor materializes, and the stricken person is whisked away by ambulance.

On a recent Shabbat, I was the guy on the floor.

My wife, Jody, and I were invited to a kiddush at a local synagogue when I started to feel faint. I sat on a bench but soon needed to lie down. I was nauseous and thought I might throw up; but when I tried to get to the bathroom, my vision blurred, and the outdoor space spun around me.

I lay down again, this time on the hard pavement, aware of the spectacle I was creating but with no real option to sit up, unless I wanted to pass out.

This being a shul full of Jews, it was inevitable that there would be a doctor in the house. My pulse was dangerously low, he warned. He asked me to count from one to 10. No confusion, but he still felt I needed to get to the ER.

“I don’t want to go,” I whispered to Jody. “I don’t want to spend the whole of Shabbat in the hospital.”

But it was too late. The ambulance had already been called. My blood pressure was a paltry 80/40. Hoisted onto a gurney, I was whisked off to Hadassah Medical Center in Jerusalem’s Ein Kerem.

The emergency room was efficient. The staff hooked me up to an IV, checked my heart with an EKG, did a chest X-ray, and took blood and urine. Everything came out normal.

“It’s probably dehydration,” the doctor pronounced as he hooked me up to a saline drip.

That didn’t make sense to me. I’ve had plenty of times when I hadn’t drunk enough, but nothing like this had ever happened. I had a couple of sips of Scotch at the kiddush – could it have been that?

My own diagnosis: I was having a panic attack. The symptoms were consistent: dizziness, shortness of breath, low blood pressure (although to the doctor’s cautious credit, those same symptoms could indicate a heart attack).

Anxiety has been my watchword since the October 7 massacre in Israel’s South. The minute-by-minute reports of fighting in Gaza that fill my WhatsApp feed, the deep depression over the fate of the Israeli hostages in Hamas’s hands, the escalation in the North has everyone on edge.

A tumor grows back

Now add to all that some unexpected health news, and maybe it’s not so surprising that I collapsed.

Remember the “boom-boom” radiation I received over the summer? It, unfortunately, didn’t work. At first, the tumor we zapped shrank, and I was optimistic.

But a follow-up PET CT was shocking: The tumor had grown back – and then some. New tumor sites appeared as well.

My doctor recommended that we start treatment again.

Follicular lymphoma is a chronic cancer. For most people, it won’t kill you, but it nearly always comes back, requiring more treatment. I had chemo and immunotherapy in 2018 and went into remission – but just for six months before I relapsed. If there’s a silver lining, I went treatment-free for five years since. With follicular lymphoma, you don’t treat it until the tumors get large enough or if you’re having “B” symptoms.

Was my near-fainting in shul a “B” symptom? My hematologist didn’t think so. But the disease is now clearly progressing, and treatment in 2024 has become unavoidable.

That’s where I am now – at the beginning of months of cancer treatment that will, hopefully, knock out the lymphoma for a good many years.

PART OF what gives me confidence is a new kind of treatment that has emerged that will, in the coming years, likely become the standard of care for blood cancers like mine. No more chemo. The new drug of choice is known as a “bispecific antibody,” a form of immunotherapy.

A quick primer: Antibodies are a protein component of the immune system that circulates in the blood, recognizes foreign substances like viruses and bacteria, and neutralizes them. Immunotherapy, unlike chemo, which indiscriminately kills both cancer and healthy innocent bystander cells, harnesses the body’s immune system to fight any malignancies. Scientists do this by engineering antibodies in a lab, and then injecting them into the patient.

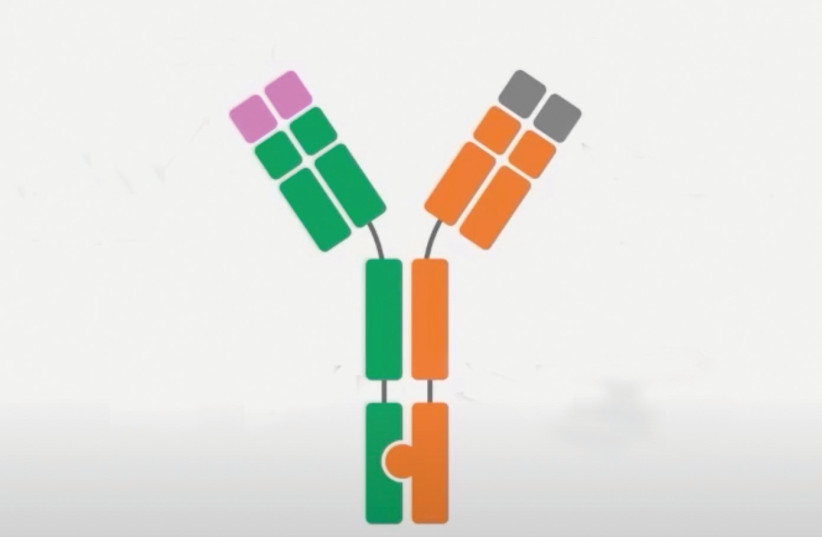

Antibodies tend to have a “Y” shape. Most engineered antibodies are monoclonal – they have the same function on each “arm” of the Y. For lymphoma, they seek out a protein called CD20 that’s expressed by the tumor cells.

For bispecifics, the two arms have different functions. One still searches for CD20 proteins, but the other binds with CD3 proteins which are expressed by T-cells in the immune system.

Because the two arms of the Y are tethered to the same stem, they pack a powerful punch. Unlike with monoclonal antibodies, where the T-cells have to search somewhat randomly throughout the body to find the cancer cells that the monoclonal antibody has marked, with bispecifics the antibody basically says, “Hey, T-cells, I found a tumor. Here it is. Go get it.”

The result can be dramatic, with tumors obliterated sometimes as quickly as a matter of minutes. We don’t know how long the remissions will last – bispecifics are so new that there’s no long-term follow-up date on them – but the prognosis is encouraging.

By this time next year, I should be done with IVs and meds. I can only pray that our country will be in a similar remission from the war and the divisiveness that preceded it, and that we will have eradicated our enemies – both internal (like cancer) and external.

The writer’s book TOTALED: The Billion-Dollar Crash of the Startup that Took on Big Auto, Big Oil and the World is available on Amazon and other online booksellers. brianblum.com