National elections were held in Iran on March 1. The results were underwhelming. It took three days for the electoral authorities to count the votes and consider the results. On March 4, Interior Minister Ahmad Vahidi told a news conference in Tehran that of Iran’s 61 million eligible voters, only some 25 million had deigned to participate. The resultant turnout of 41% would be the lowest ever recorded in post-revolution Iran.

Even so, the BBC published comments from voters skeptical of the official announcement. One said: “It’s not the real result.” Another woman declared “People believe it’s actually less than 41%.” When asked what she thought the true turnout had been, she said comments on Instagram suggested as low as 20%. “Some even say 15%,” she added.

Some experts agreed. “The real turnout is likely lower,” wrote Alex Vatanka, founding director of the Iran Program at the Middle East Institute in Washington, “although it is impossible to know at this stage.” The Stimson Center was even more circumspect. “Due to press and media censorship,” it commented, “as well as the absence of independent observers, it is challenging to verify the authenticity of these statistics.”

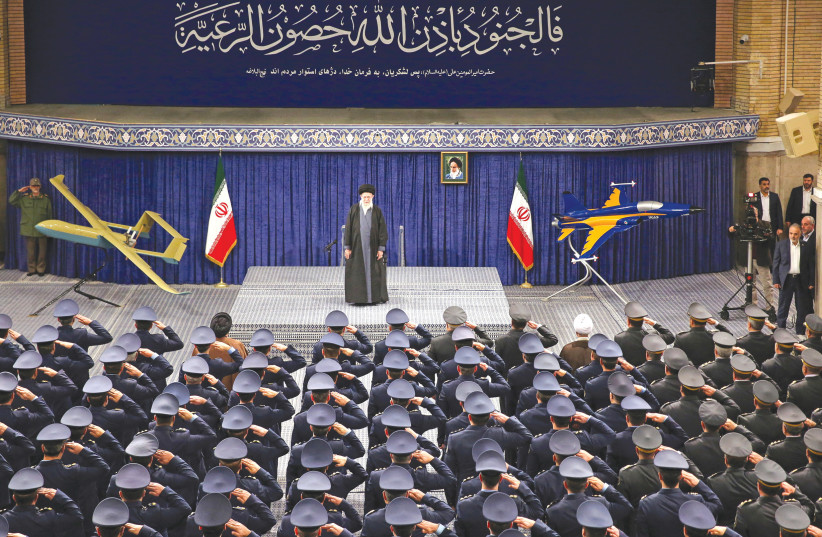

The poll was held to elect the 290 members of the national parliament, the Majles, and the 88 clerics who make up the Assembly of Experts, composed exclusively of male Islamic scholars. Each member of the assembly will sit for a term of eight years and, should the occasion arise, be tasked with selecting the country’s supreme leader. The occasion may indeed arise. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is 85 years old, and rumors about his health have been circulating since 2022.

The election results indicate that conservative politicians will dominate the next parliament, which is scarcely surprising given the tightly controlled procedures under which candidates are vetted as suitable to run in the elections. This preelection task is undertaken by the country’s constitutional watchdog, the powerful Guardian Council, half of whose members are directly selected by Khamenei.

In fact, of the 15,200 people who registered to stand in the election, no fewer than 7,296 were disqualified, some of them well-known critics of the regime, many of them moderates and reformers.

Iranian women have demonstrated more than once to the regime that they are a force to be reckoned with, and the Guardian Council acknowledged reality by allowing 666 women to stand.

Boycotting the polls

The popular mood during the preelection campaign was somber. Powerful voices called on the nation to boycott the forthcoming polls. One with particular appeal was that of the imprisoned Narges Mohammadi, who won the 2023 Nobel Peace Prize for her work fighting the oppression of women in Iran. She denounced the elections as a sham, following what she called the “ruthless and brutal suppression” of the 2022 protests triggered by the death in custody of Mahsa Amini, arrested for wearing her hijab “improperly.

Mohammadi, a human rights activist, has been arrested 13 times and sentenced to a total of 31 years in prison. Having already spent some 12 years in jail serving multiple sentences, Iran’s Revolutionary Court sentenced her, in January, to an additional 15 months in prison, doubtless in retaliation for what occurred at the Nobel Peace Award ceremony in December.

Her children had traveled to Stockholm to accept the Nobel award on her behalf. In her speech, smuggled out of prison and read out on her behalf, she denounced Iran’s “tyrannical” government. Referring to the 2022 protests, Hamodia said young Iranians had “transformed the streets and public spaces into a place of widespread civil resistance.”

Freedom of expression was a major issue during preelection campaigning. Iranians are well aware of the growing numbers of journalists, artists, and other activists being arrested. The suppression of political dissent is also resented. The most prominent figure in the Green Movement, Mir-Hossein Mousavi, who was a presidential candidate in 2009, remains under permanent house arrest.

In 2021, for a variety of reasons, it suited Supreme Leader Khamenei to approve the election of Hassan Rouhani as president, despite the fact that many in Iran regard him as a moderate. He has since fallen out of favor.

Disqualified from running for the Assembly of Experts after 24 years of membership, Rouhani nonetheless cast his vote on election day. Another former president, the reformist Mohammad Khatami was, according to the Reform Front coalition, among those who abstained from voting. On his official website, Khatami posted that Iran is “very far from free and competitive elections.”

The head of Reform Front, Azar Mansouri, said she hoped the state would learn its lesson from the low turnout, and change the way it governed the nation.

The respected London-based think tank, Chatham House, maintains that these Iranian elections “should not be seen as a democratic exercise where people express their will at the ballot box. As in many authoritarian countries, elections in Iran have long been used to legitimize the power and influence of the ruling elite.”

The regime, it says, has failed to learn any lessons from the nationwide protests in 2022 following the Mahsa Amini affair and the subsequent brutal government crackdown. Rather than attempting to build back popular legitimacy through inclusive elections, the think tank concludes, the political establishment has prioritized a further consolidation of conservative power across both elected and unelected institutions.

Confirming his reputation for turning the truth on its head, on March 5 Supreme Leader Khamenei hailed Iran’s elections as “great and epic,” despite the boycott by a large majority of voters. “The Iranian nation did a jihad and fulfilled their social and civil duties,” he declared.

In response, reformist lawyer and former member of parliament Mahmoud Sadeghi tweeted: “Don’t the sixty percent who did not vote count as Iranians?”

Writing from Tehran’s Evin prison, where he has spent more than eight years behind bars, dissident reformist politician Mostafa Tajzadeh, an outspoken critic of Khamenei, called the elections “engineered” and a “historic failure” of the system and of the Supreme Leader. Yet this perverse manipulation of the founding principle of Western democracy – free and fair elections – is how Iran’s regime maintains its unyielding grip on power.

The writer is the Middle East correspondent for Eurasia Review. His latest book is Trump and the Holy Land: 2016-2020. Follow him at: www.a-mid-east-journal.blogspot.com.