Israel’s conversion crisis is becoming an aliyah crisis - opinion

The gates of aliyah and the gates of conversion were meant to stand side by side. It is time to open them both.

The gates of aliyah and the gates of conversion were meant to stand side by side. It is time to open them both.

We can recognize this as the moment to forge new relationships with those who share our values and turn the page toward a new and inspiring era of Universal Zionism

Bennett’s campaign leans on critique and rhetoric, offering little clarity on policy, governance, or Israel’s future direction.

The attacks have broadened to include assaults on all religious women who do 'only' national service and religious men who do 'only' hesder service, alternating yeshiva learning and active service.

President Donald Trump’s 2019 recognition of Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights sparked global debate over law, history, and security.

After the October 7 massacre, Gaza faces a choice: rebuild with realism and deradicalization, or pave the way for the next war.

Iran has learned from Trump’s 2025 tactics, using contradictory signals to control nuclear talks and keep the US off balance.

The West keeps mistaking regime survival tactics for reform; the Iranians know better and have paid with their lives.

For too long, too many religious Jews have been asked to choose between loving our people and fulfilling our values.

For the first time during the war, a major international organization has publicly recognized the presence of armed groups operating within a Gaza hospital.

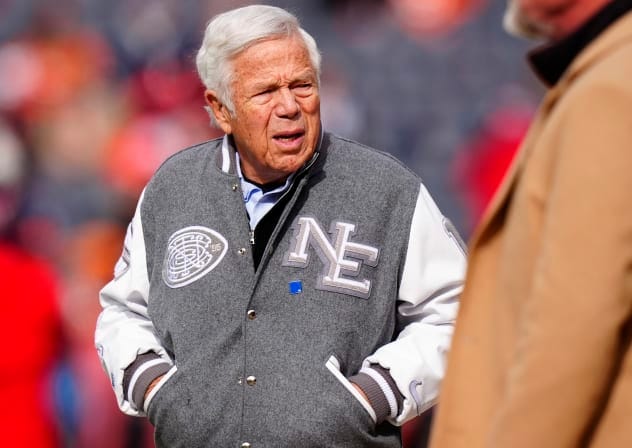

Robert Kraft's $15M Super Bowl ad depicts Jews as powerless; real survival demands strength, confidence, and self-defense, not sympathy.