It could almost be the beginning of a joke: What do bats, priests, and rabbis have in common?

The answer is that their social networks can be traced using a new computer science tool called network analysis. Interdisciplinary collaborating between a Talmud scholar at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Beersheba and a zoologist at Tel Aviv University presents a whole new way of analyzing Judeo-Christian relations.

Prof. Michal Bar-Asher Siegal of BGU and Prof. Yossi Yovel of TAU don’t usually work together on a single project. But Yovel is an expert in network analysis that he uses to research bats. With Bar-Asher Siegal, they thought of the “crazy” idea to apply his methodologies for examining Judeo-Christian relations in the literature from the early first centuries CE.

Proof of concept

Their proof of concept has just been published in the prestigious Nature group’s journal Humanities and Social Sciences Communications under the title “Network analysis reveals insights about the interconnections of Judaism and Christianity in the first centuries CE.”

Using passages from the Babylonian Talmud and Christian texts from the 1st to the 6th centuries that Bar-Asher Siegal had previously analyzed, they performed the first network analysis of textual parallels of Christian writings and Jewish sources. Network analysis is a method of studying the relationships among entities in a network and involves analyzing the links among entities and the characteristics of the entities themselves.

Until recently, this question was explored with the limited source material and limited tools to analyze it.

While working on a limited set of data from a specific corpus, this project offered a new set of methodological tools, borrowed from computer sciences, that could ultimately serve for understanding the connections between Jews and Christians in late antiquity.

Complex intertwined evolution

“We generated models of inter-religious Christian–Jewish networks that demonstrate the scope, nature, and advantages of network analysis for revealing the complex intertwined evolution of the two religions. The Jewish corpora chosen for this research are rabbinic writings from late antique Babylonia and Palestine. Christian texts range from the first through sixth centuries CE. Instead of representing interactions between people or places, as is typically done with social networks, we model literary interactions that, in our view, indicate historical connections between religious communities. This novel approach allows us to visually represent sets of temporal/spatial/contextual relationships, that evolved over hundreds of years, in single snapshots. It also reveals new insights about the relationships between the two communities,” they wrote.

“Our study shows that network analysis of textual parallels using the tools of computer science yield wondrous results. We believe it will really open up the study of relations between the two religions in the beginning of the common era. It has already yielded new insights when applied to our small sample of texts. Who knows what exciting discoveries await when we analyze larger amounts of text,” she added.

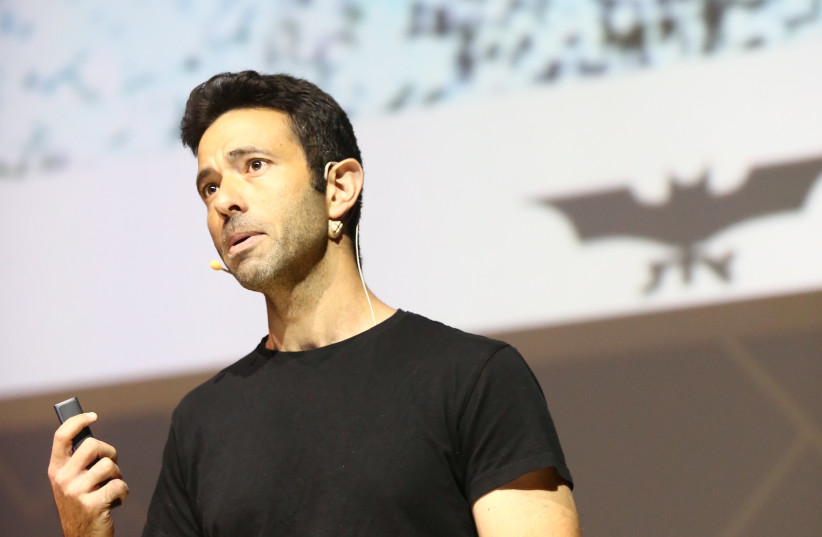

“This is a good example of how interdisciplinarity and the use of tools from one scientific field can enrich another,” noted Yovel.

While network analysis is not new in the field of digital humanities, it is new to the study of rabbinic and Christian literary interactions.

This is the first time an automated analysis of textual parallels was accomplished, according to the researchers. One of the fascinating benefits of this novel approach is the visualization of the relationships between Jewish and Christian writings to represent sets of temporal-spatial-contextual relationships, which evolved over hundreds of years, in single snapshots.

“The visualizations allow us both to get a clearer picture of the interactions and look at them in new ways, which prompted new insights,” Bar-Asher Siegal said.

“The development of the two religions – Judaism and Christianity – is a topic of much debate. Whereas they are known as separate religions, in fact, these two religions developed side by side. The evolution of relations between Judaism and Christianity has often been characterized as a ‘parting of the ways’ where, after a specific point, the two religions began to develop independently.”

While recent scholarly research has challenged that idea, these new visualizations really bring to light how the two religions developed in parallel and in dialogue, not separately, they wrote.

“The application of network analysis makes it possible to identify the most influential texts – that is, the key ‘nodes’ – testifying to the importance of certain traditions for both religious communities. What did the Jews know? The New Testament or later sources? And which parts of the New Testament? This leads to interesting scholarly questions – Why these texts and not others? How did they know and how did they react to this knowledge?” continued Bar-Asher Siegal.

“The networks we created reveal that rabbinic sources mock and argue against early Christian sources, but less so when it comes to later ones. Moreover, network analysis suggests a correlation between text, time, and geography. Namely, Jewish sources are familiar with early, eastern Christian sources, but they show wider geographical familiarity with both eastern and western Christian sources in later periods,” concluded Bar-Asher Siegal.