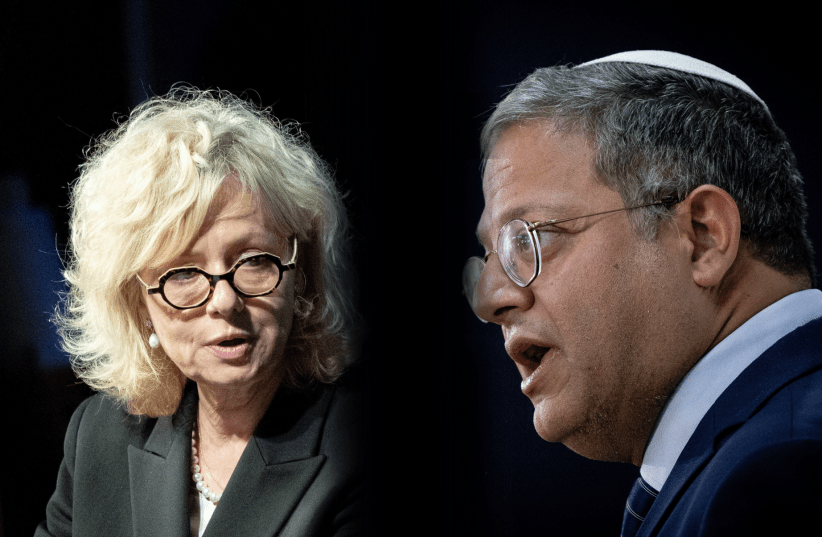

National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir's actions during protests against the government's judicial reforms raise "real concern" that he crossed the line in "attempting to intervene in Israel Police's independent discretion," Attorney-General Gali Baharav-Miara wrote in an opinion filed as part of the ongoing court case against the constitutionality of Ben-Gvir's Police Law.

The attorney-general wrote that Ben-Gvir could have crossed the line between setting general policy regarding protests, which the law permits, and "intervening or attempting to intervene in the professional and independent discretion given to Israel's Police's commanding officer on the ground, including regarding specific events in real-time,"

According to the attorney-general, on a number of occasions, the national security minister attempted to intervene in operational events on the ground, which the law does not permit. These include his announcement on March 9 of the decision to remove Tel Aviv Police Chief Ami Eshed from his position, just hours after criticizing Eshed's handling of a protest against the judicial reforms, and while the protest was still ongoing; his contacting a number of other police commanders during the same protest in real-time, to express his dissatisfaction with their conduct; his directive during a March 1 protest against the judicial reforms, to open roadblocks of specific roads, during and because of protests occurring there; and more.

A-G: Ben-Gvir's orders 'pretend' to be policy decisions

While Ben-Gvir described these as "policy decisions" that are permitted by law, they essentially were direct or indirect operational orders "pretending" to be policy decisions, the attorney-general wrote.

"Therefore, it is important that the setting of policy occurs as part of routine [activity], based on detailed and completely factual and professional foundations and after hearing the professional echelon, especially based on a conversation with the police commissioner. In any case, policy is not formulated based on a single event, and surely not during such event," Baharav-Miara wrote.

The attorney-general also included Ben-Gvir's own opinion. The national security minister argued that his policy was simply to apply equal enforcement to all protests – and therefore roadblocks of major transportation arteries should not be permitted, and he expected the police to respect this. Ben-Gvir also repeated a claim he has made many times in the past week, that Baharav-Miara was biased against him and his Otzma Yehudit party and was acting from a political, and not professional, position.

"The appellants cry for anarchy, the appellants call for roadblocks, the appellants want chaos, and they also want the national security minister to serve as a plant and not to speak, nor defend the rule of law," Ben-Gvir wrote.

Ben-Gvir's Police Law

The opinion came as part of an ongoing appeal against Ben-Gvir's Police Law, the first section of which passed into law on December 28. The law anchors the Israel Police's subordination to the government, as well as the national security minister's ability to set policy and general principles. It also enables the minister to set policy regarding investigations, after consulting with the Attorney-General, the police commissioner and the officers responsible for investigations. Finally, it requires the national security minister to publish his policies online.

Baharav-Miara pointed out that in the opinion that no policies had been published online as of yet.

The second section of the law, which is currently being prepared for its second and third readings on the Knesset floor, and is considered more problematic, determines the police commissioner's authorities, as opposed to the police in general. The bill stipulates that the commissioner serves under the government's authority but is "subordinate" to the national security minister. The bill adds that the commissioner is the highest commanding officer of the police. It also gives the national security minister the power to set policy regarding the "duration of cases".

The appeals, by the Movement for Quality Government in Israel and the Association for Civil Rights in Israel, which were filed soon after the first section passed, claim that the law gives too much power to the government and ministers over the police.