When Moti Aksmit, a spokesman for the Israel Basketball Association, and Oren Smadja, the legendary Israeli judoka, met up in 2020 for a work meeting, they never imagined that it would lead to a two-year adventure that would culminate in the recent publication of the book Trailblazer: Oren Smadja’s Judo Marathon.

“While we were sitting together at the meeting, Oren suddenly turned to me and said, ‘I have a lifelong dream to write a book,’” Aksmit recalls. “So I asked him, ‘What’s the problem?’ and he replied that he wouldn’t know where to begin. Just one week later, we began working on the book together.”

The book tells the life story of Smadja and his father, Maurice, now 91. “While carrying out research for the book with Oren and the people who work with him, I started learning more about Maurice Smadja. That’s when I got the idea to write the book about how Israel became a judo powerhouse.

“The story of Israeli judo begins with both Maurice and Oren Smadja. Without these two, the judo scene in Israel would not have become anywhere near as successful as it currently is,” says Aksmit.

“The story of Israeli judo begins with both Maurice and Oren Smadja. Without these two, the judo scene in Israel would not have become anywhere near as successful as it currently is.”

Moti Aksmit

What is so special about Oren that led him to become a trailblazer?

I’m a big fan of Oren’s – I adore his personality and everything about him. In my mind, he is a role model of international caliber. Oren Smadja has been a trailblazer his entire life, including as a young determined athlete who took home an Olympic bronze medal when he was just 22. Since then, he has been achieving other goals, one after another. His whole way of thinking and the way he has been galvanizing the Israeli judo world are absolutely incredible.

SMADJA WAS was born in 1970 in Ofakim and grew up in Moshav Nordia in the Sharon region. His father, an immigrant from Tunisia, was the founder of the sport of judo in Israel. When he was 17, Smadja began participating in international competitions and joined Israel’s National Judo Team.

He is one of the first two Israelis to win Olympic medals, winning the bronze in Barcelona in 1992 (Yael Arad won the silver medal the previous day). Then, in 1995, he secured the silver medal at the World Championships in Chiba, Japan. Moreover, he was the first Israeli to win an Olympic medal as an Olympic athlete and as a coach (Rio de Janeiro 2016, and Tokyo 2020).

In 1996, Smadja founded the Israel Judo Association in Even Yehuda and began training hundreds of young athletes. In 2010, he began training Israel’s men’s national judo team. At the 2016 Olympics, Ori Sasson, a Smadja trainee, won the bronze medal. At the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, under the direction of Smadja and Israel’s women’s coach Shany Hershko, the Israel National Team won the bronze medal.

“I had to overcome numerous difficulties along the way, but I never viewed them as problems that could stop me from reaching my goals. I won an Olympic medal, but I was still disappointed that I didn’t get the gold,” says Smadja.

“At the time, my plan was to continue competing so that I could win the gold medal, too. When that didn’t work out, I realized it was time for me to move on to the next phase in my life. That’s when I opened the Judo Club in Israel so that I could train Israel’s future judo Olympians, just like my father had.

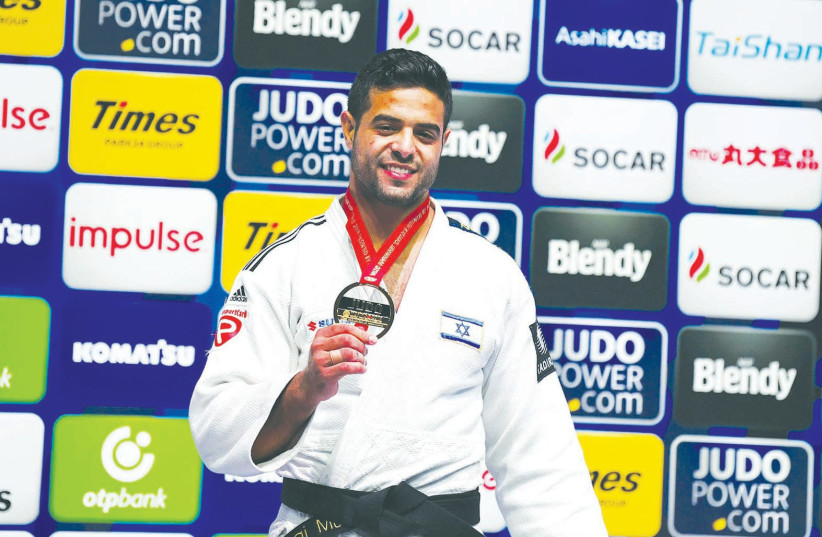

“To take a little boy like Sagi Muki, when he was only four years old, and train him to be a World Judo Champion [August 2019] is, to my mind, the best example of trailblazing,” Smadja proclaims.

“Ori Sasson, who I also trained, loves to tell how on his first day on the national team – when I came in to welcome the athletes – I told them that I was planning to change the face of Israel’s national sports teams. Apparently, they were awestruck and just stood there staring at me. And what happened? I trained them, and they brought home the group bronze medal from the 2020 Tokyo Olympics – the first time an Israeli group ever won a medal,” Smadja adds proudly.

How do your feelings differ from winning an Olympic medal as an athlete, as opposed to winning a medal as a coach?

Yael Arad and I were the first Israelis to ever win an Olympic medal. What can I say – the feeling was out of this world. I threw my arms up with so much excitement and pride.

When Sasson won the bronze medal at Rio de Janeiro in 2016, I grabbed the side of my head with my hands, absolutely crazy excited that I was the one who helped an athlete win an Olympic medal.

I don’t think I can explain in words the enormous satisfaction a person can feel when he succeeds in achieving the unbelievable. Judo is an entire world that requires supervision, hard work and a special way of life.

FROM A very young age, judo was the center of Smadja’s world. “It all began in the neighborhood bomb shelter with my father in Ofakim, in the neighborhood where I grew,” Smadja recalls. “As a little kid, I used to train a lot, and I didn’t feel different from all the other kids. But as I got older and began competing, I realized that I was talented in the sport and that I was able to carry out the moves my father had taught me in a much more exact way,and with more precision than the other kids.

“Nothing came easy, and I would spend hours and hours trying to perfect my moves. I participated in my first competition when I was 12, winning the gold medal at the Israel National Championship.

“The first international competition I joined was in Sweden, and I won a gold medal there, too. It was at that point that I realized I had been born with a special gift. In 1988, my father sat me down for a talk. He told me, ‘Four years from now, you are going to win an Olympic medal.’ I searched his eyes, trying to figure out if he was hallucinating or something, since at the time Israel didn’t even have a national judo team.

“But, lo and behold, from 1988 until 1992, for four straight years, I pushed forward with unrestrained force. I moved to Tel Aviv, changed my lifestyle and did everything I could to prepare myself for winning an Olympic medal. I had a goal, and I was crystal clear about how I wanted to achieve it.”

What do you remember about the day you won the bronze medal at the Olympics?

There are so many things you must be aware of before a competition, and it’s critical to be extremely precise and exact about everything. Many people say that when I won the medal, I looked like I was in shock, but I wasn’t. Granted, this was the first time I had ever won an Olympic medal, and this was a huge win for Israel. But I think for me, along with my humility and the way I was raised, this had been my goal and I had worked hard to reach this place, so it actually seemed quite natural that I would win a medal.

Only when I returned home did the magnitude of my accomplishment begin to sink in: Half of the country was at the airport to welcome us, and from that moment on I was a celebrity. It was very uncomfortable for me to walk around and draw so much media attention. I really had not wanted to become someone famous.

The first thing I did when I got back home was to go to my parents’ house so I could be with my family and the people who had helped me during this journey.

I was the first person to win an Olympic medal as an athlete and as a coach. I was the first coach to lead a team to win a group medal. But I’m not in it for the publicity; I’m much less interested in that. I’ve been married for 25 years and have three children. I live a quiet, calm life, and that makes me very happy.

One of the most important messages that I wanted to get across in the book was that you don’t need to be born with a silver spoon in your mouth to succeed. What you do need is a loving family that is willing to support you – that’s what gives people hope at the beginning of their journey.

ADDS AKSMIT, the book’s co-author, “The second message is that the only way to achieve a lofty goal – and this is true for any field, not just sports – you need faith and motivation. I wanted to paint a picture of a boy who started from the bottom and climbed his way up the ladder to the pinnacle of success. A boy who grew up in a warm, close-knit family living in Israel’s periphery.

“Oren spent hours on the bus traveling back and forth from the Wingate Institute for his training sessions. He was incredibly determined and had to overcome many obstacles along the way to success. I wanted to explain to children and teens who read this book that if you want to get somewhere in life, you first have to believe in what you’re doing and be willing to persevere. If you do that, then you might just reach your goal in the end.”

DURING HIS career as coach of Israel’s National Judo Team, Smadja has succeeded in training a number of athletes who attained international achievements, such as Sasson, Muki and Peter Paltchik.

“When I retire, I will not remember my achievements, only my failures,” Smadja admits. “I’ve had a few misses that still sit heavily on my heart. There were two other athletes who trained alongside Sasson and competed in the Olympics: Muki in 2016 and Baruch Shmailov in 2021. Both got so close to attaining an Olympic medal, and I cannot help but imagine what it would have been like if they had succeeded.

“Plus, two more athletes who trained with us competed in the World Championship. In Israel, the media goes crazy over athletes who come home with medals and blows these successes way out of proportion. But when athletes reach incredible achievements and ‘almost’ win, not one word is ever mentioned about them. To my mind, however, bringing an athlete to this level of success is also a great achievement.

“We managed to raise the status of Israel’s National Judo Team to such a high level that not achieving an Olympic medal or at least a European Championship medal is considered a disappointment. The next generation will have very large shoes to fill.

“My goal is to continue the heritage my father began. People all over the world have heard about our success in judo and are curious what we did to achieve it. For over a decade now, Israeli athletes have been coming home with more and more medals. We can instill this goal in the minds of Israeli children when they are very young – and not just regarding judo but in all different types of sports. We can copy this model for many other Olympic categories and begin seeing success in them, too.”

Does the fact that you competed in the Olympic games make your connection with athletes that train with you stronger?

My trainees and I have formed a deep bond of mutual respect. As a former athlete, I understand everything they’re going through. If I didn’t love the athletes that I’m training and without a passionate belief in Zionism, there’s no way we would be able to succeed. The secret to success, in my opinion, is having something that motivates you.

Have you had a chance to meet Culture and Sport Minister Miki Zohar?

Yes, I’ve had the privilege to meet a number of Israel’s prime ministers and members of Knesset. I recently met Tourism Minister Haim Katz, and we had a fantastic conversation. I was surprised to learn that he’d been following my career for years, and even knew the name of my dog.

I had an extremely professional conversation with Miki Zohar, during which we discussed our detailed goals and the difficulties we are striving to overcome. Nowadays, Knesset ministers are more attentive to the benefits of having strong national sports teams. I hope that once we are allocated the funds and infrastructure that Miki has proposed, we will reach even greater achievements. I wish him lots of success.

I personally hope to always be involved in the promotion of sports in Israel. ■

Translated by Hannah Hochner.