A groundbreaking study has uncovered 14,000 unique sites in the DNA that together form the most elementary blueprint for embryogenesis – the creation of embryos.

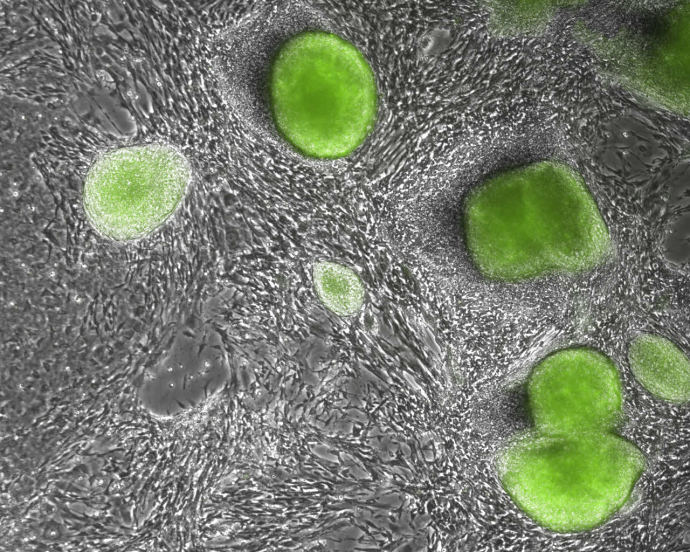

Skin cells taken from an unused embryo can be reprogrammed into other types of cells, as artificial embryonic stem cells made from them are identical to natural stem cells that develop at the earliest stages of the embryonic development process and are responsible for the development of all the cells of a fetus. However, they cannot create embryonic tissues that are outside the embryo such as the placenta.

The findings of the study – led by Prof. Yossi Buganim at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem Faculty of Medicine’s Institute for Medical Research and Prof. Tommy Kaplan at HU’s School of Computer Science and Engineering and Department of Computational Biology – have just been published in the prestigious journal Nature Communications under the title “Comparative parallel multi-omics analysis during the induction of pluripotent and trophectoderm states.”

In 2006, Japanese scientists inserted four embryonic genes into skin cells and successfully reprogrammed them to act like embryonic stem cells.

In 2015, Buganim and his team were the first in the world to discover how to create artificial placental stem cells from skin cells. This step makes it possible for scientists to create the two earliest types of stem cells in the embryonic development process that happens right after sperm fertilizes an egg.

Examining the process

The HU research team, which included doctoral students Mohammad Jaber, Ahmed Radwan and Netanel Loyfer, closely examined the process that skin cells undergo to transform themselves into either embryonic or placental stem cells.

“We analyzed the changes that skin cells undergo to change their identity and become one of the two earliest types of stem cells,” Buganim explained. “We also looked at changes in gene expression of the skin cell, in the accessibility and activity of the DNA within the nucleus of the changing skin cell and in epigenetic markers (marks that ‘decorate’ the DNA and are responsible for gene expression). These are all critical when trying to convert a skin cell into an artificial embryonic or placental stem cell.”

The researchers found that the changes that take place in skin cells to become either embryonic or placental artificial stem cells were entirely different from one another at every level, despite the fact that both started out as skin cells.

When a skin cell transforms into an artificial embryonic stem cell, the parts of DNA that are responsible to create the brain, heart and liver begin to reorganize and prepare themselves to differentiate, when given the right signal, into brain, heart or liver cells. On the other hand, when those same cells were transforming into an artificial placental stem cell, the DNA sites began reorganizing themselves to allow the changing cell to implant itself and attract blood vessels – a phenomenon that occurs naturally, allowing the embryo to implant into the uterus.

Remarkable discovery

The most remarkable discovery came when the team compared the two processes side-by-side and looked at a chemical molecule called methyl, which interacts with specific areas of the DNA and is responsible for silencing their expression. “We discovered that artificial placental stem cells contained close to 14,000 DNA sites with methyl but were nowhere to be seen in the artificial embryonic stem cells,” reported Buganim.

“We discovered that artificial placental stem cells contained close to 14,000 DNA sites with methyl but were nowhere to be seen in the artificial embryonic stem cells.”

ggg

When the research team tried to understand the significance of those DNA areas, they found that they are responsible for creating all the organs and cells in developing embryos – from the brain, heart, liver and kidneys to the skeleton, spinal cord and connective tissues.

Going forward, this significant discovery may help explain the embryonic defense system, which prevents early placental cells from developing into embryonic ones. “Since placental cells are susceptible to damage and infection, the body’s natural defense mechanism prevents placental cells from migrating to the developing embryo and attaching to it to become part of the embryo,” Buganim concluded.

“Overall, this study illuminates key features that characterize our ability to reprogram cells and provides a powerful tool to study cellular plasticity and cell-fate decisions.”